DIC Score Calculator

Clinical Assessment

Drug-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation isn’t something you see every day-but when it happens, it kills fast. It doesn’t come with a warning label. No rash. No fever. Just a slow unraveling of the body’s ability to control bleeding and clotting at the same time. And it’s rising. In oncology units, ICUs, and even outpatient infusion centers, clinicians are seeing more cases tied to newer cancer drugs, anticoagulants, and antibiotics. The mortality rate? Between 40% and 60%. If you miss it, the patient won’t make it to morning.

What Exactly Is Drug-Induced DIC?

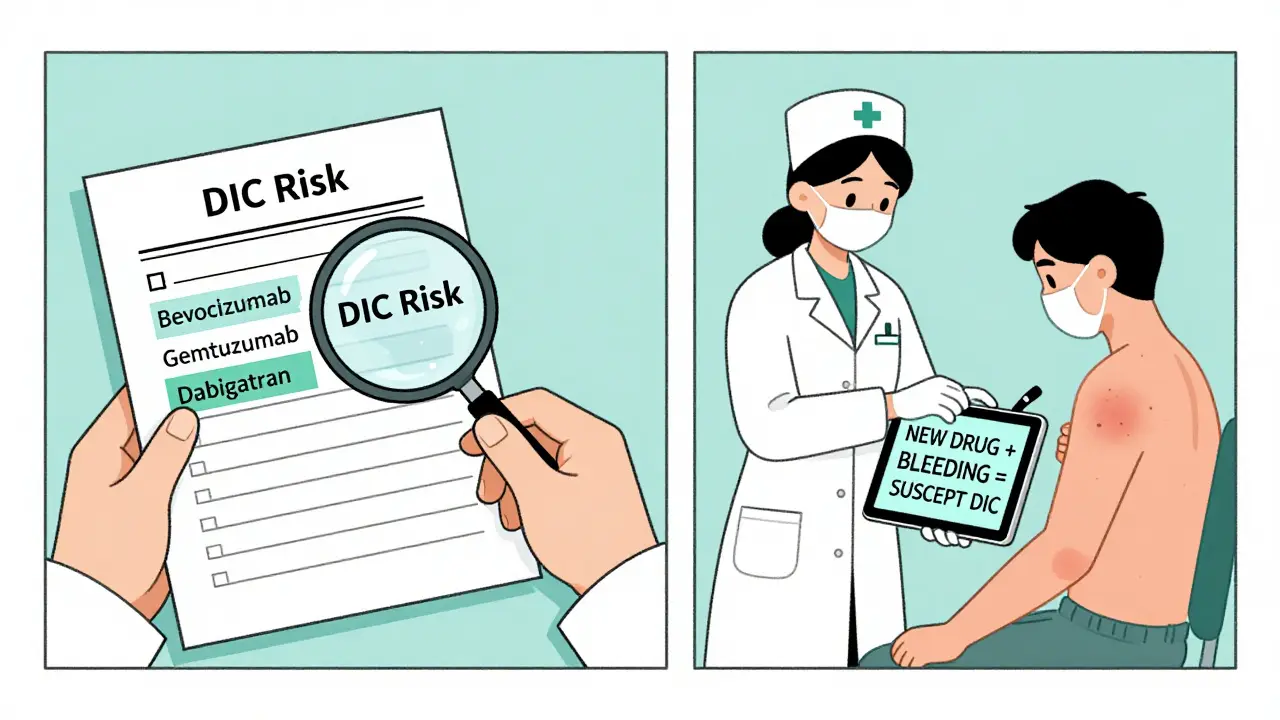

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) isn’t a disease. It’s a syndrome. A cascade. A system-wide meltdown of the coagulation system triggered by something else-in this case, a medication. The body starts clotting everywhere at once: in tiny blood vessels, in the lungs, in the kidneys. That sounds like it should stop bleeding, right? Wrong. All that clotting burns through platelets and clotting factors. Once they’re gone, the body can’t clot anywhere-even when it needs to. The result? Massive, uncontrolled bleeding. The most common culprits? Anticancer drugs like oxaliplatin, bevacizumab, and gemtuzumab ozogamicin. Anticoagulants like dabigatran. Even antibiotics like vancomycin. A 2020 analysis of over 4,600 global adverse drug reaction reports found that 88 drugs have a clear link to DIC. And here’s the scary part: most of these drugs don’t even list DIC as a known risk in their prescribing information.How Do You Spot It?

DIC doesn’t announce itself with a bell. It creeps in. A patient on chemotherapy starts bleeding from their IV site. Their platelet count drops from 180 to 65 in 48 hours. Their PT and aPTT start creeping up. Their D-dimer? So high it’s off the scale. Fibrinogen? Plummeting below 1.5 g/L. These aren’t random lab values. They’re the fingerprints of DIC. The International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) has a scoring system that turns these numbers into a diagnosis:- Platelet count: 100-180 = 0 points; 50-99 = 1 point; <50 = 2 points

- Prothrombin time: 3-6 seconds longer than normal = 1 point; >6 seconds = 2 points

- Fibrin degradation products: Mildly elevated = 1; moderately elevated = 2; strongly elevated = 3

- Fibrinogen: >1.0 g/L = 0; <1.0 g/L = 1

What Drugs Are Most Likely to Cause It?

Not all drugs are equal. Some have a 1 in 100 chance. Others? 1 in 1,000. But when they hit, they hit hard.- Bevacizumab (Avastin): ROR 2.02. A monoclonal antibody used in colorectal and lung cancer. Causes endothelial damage. DIC can strike within days of the first dose.

- Oxaliplatin: ROR 1.77. Common in GI cancers. Often triggers DIC after multiple cycles. Case reports show patients needing 6 units of platelets a day.

- Gemtuzumab ozogamicin: ROR 28.7. The highest-risk drug on record. Up to 10% of patients develop severe DIC. Often fatal if not caught immediately.

- Dabigatran (Pradaxa): ROR 1.34. An oral anticoagulant. DIC here is rare-but when it happens, it’s aggressive. Requires immediate reversal with idarucizumab.

- Vancomycin: ROR 1.5. Surprisingly common. Especially in patients with renal failure or those on high doses.

Management: Stop the Drug. Support the Body. No Guesswork.

There’s only one rule: stop the drug immediately. No exceptions. No waiting for labs. No hoping it’s just a low platelet count. If you suspect drug-induced DIC, discontinue the medication the moment the suspicion arises. Supportive care is everything. You’re not curing DIC. You’re keeping the patient alive until their body recovers.- Platelets: Give if count is below 50 × 10⁹/L and there’s active bleeding or planned procedure. If bleeding is minor or absent, 20 × 10⁹/L is enough.

- Fibrinogen: Maintain above 1.5 g/L. Use fibrinogen concentrate or cryoprecipitate. Below 80 mg/dL? Stop DVT prophylaxis-it could trigger a clotting storm.

- FFP and cryoprecipitate: Used to replace clotting factors. FFP for PT/aPTT correction. Cryoprecipitate for fibrinogen.

- Red blood cells: For ongoing bleeding. Monitor hemoglobin every 4-6 hours in acute phase.

What About Anticoagulants Like Heparin?

This is where things get tricky. In sepsis-induced DIC, heparin is sometimes used to prevent microclots. But in drug-induced DIC? It’s not routine. And it’s dangerous if you don’t know why you’re giving it. Heparin is contraindicated if the drug causing DIC is heparin itself (heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, or HIT). HIT looks exactly like DIC-low platelets, clots, bleeding. But the treatment is completely different. You stop heparin. You use argatroban or bivalirudin. Give heparin here? You make it worse. Studies on antithrombin III and thrombomodulin show possible benefit-but only in patients not already on heparin. That’s a clue: if you’re going to use anticoagulants, you need to be very selective. Most experts agree: don’t use them unless the patient is developing massive thrombosis without bleeding. And even then, proceed with extreme caution.What to Avoid

Some things sound logical but are deadly.- Warfarin: Never use in acute DIC. It depletes protein C and S first. That creates a temporary hypercoagulable state. You can trigger skin necrosis or worsen clots.

- Antiplatelet drugs: Aspirin, clopidogrel-stop them. They add to bleeding risk.

- Delaying drug discontinuation: This is the #1 mistake. Every hour counts.

- Ignoring the medication history: A patient with DIC? Ask: “What did they start in the last 72 hours?” That’s often the answer.

Real Cases. Real Consequences.

A 62-year-old man with colon cancer gets his third cycle of oxaliplatin. Two days later, he bleeds from his gums. His platelets are 48. PT is 22 seconds. Fibrinogen is 0.9. D-dimer is 15x normal. He’s in DIC. The oncologist hesitates-maybe it’s just chemotherapy side effects. He gives another dose. The patient codes 18 hours later. Another case: a 58-year-old woman on dabigatran for atrial fibrillation develops unexplained bruising. Her platelets drop to 32. She’s transferred to ICU. Idarucizumab is given. Fibrinogen is replaced. She survives. Why? Because her pharmacist flagged the drug as a potential trigger. Someone asked the right question. A Reddit thread from an ICU nurse in Chicago: “I’ve seen 12 cases of drug-induced DIC. 7 died. All of them had a new drug started within 48 hours. All of them had a delayed diagnosis.”How to Prevent It

Prevention starts with awareness.- For high-risk drugs like bevacizumab or gemtuzumab, order baseline and weekly CBC with coagulation panel (PT, aPTT, fibrinogen, D-dimer).

- When a patient develops unexplained thrombocytopenia or bleeding, always ask: “What’s new?”

- Update your hospital’s electronic alert system to flag patients on drugs with known DIC risk.

- Train nurses and pharmacists to recognize early signs. They’re often the first to notice.

The Bottom Line

Drug-induced DIC is rare-but deadly. It doesn’t care if you’re busy, tired, or unsure. It kills silently. The keys to survival are simple: know the drugs, recognize the signs, stop the drug, support the patient. No fancy drugs. No magic bullets. Just speed, vigilance, and the discipline to act before the numbers confirm it. Mortality is high. But it’s not inevitable. In centers where protocols are followed, survival jumps from 40% to 65%. That’s not luck. That’s systematic care. If you’re managing a patient on one of these drugs and they start bleeding or their platelets drop-don’t wait. Don’t order more tests. Don’t consult tomorrow. Stop the drug. Now. Call hematology. Start transfusions. Save a life.Can DIC be caused by over-the-counter medications?

Rarely, but yes. While most cases come from prescription drugs like chemotherapy agents or anticoagulants, there are documented cases linked to high-dose herbal supplements (like green tea extract or certain weight-loss formulas) and even excessive use of NSAIDs in patients with pre-existing clotting disorders. The risk is extremely low, but not zero.

How long does it take for DIC to develop after taking a triggering drug?

It can happen as quickly as a few hours after the first dose, especially with drugs like gemtuzumab ozogamicin. More commonly, it develops over 2-7 days. For drugs like oxaliplatin, it often appears after multiple cycles. The timing depends on the drug’s mechanism and the patient’s metabolism.

Is DIC always fatal?

No, but it’s often fatal if not treated immediately. Mortality ranges from 40% to 60% in severe cases, especially with multiorgan failure. Early recognition and stopping the triggering drug can improve survival to 65% or higher. The biggest predictor of death is delay in diagnosis.

Can DIC recur if the same drug is restarted?

Absolutely. Restarting the triggering drug almost always causes DIC to return, often more severely. Once a patient has had drug-induced DIC from a specific medication, that drug is permanently contraindicated. There is no safe rechallenge.

What lab test is the most reliable for diagnosing DIC?

No single test confirms DIC. But a combination of falling fibrinogen, rising D-dimer, low platelets, and prolonged PT/aPTT is the hallmark. D-dimer levels more than 10 times the upper limit of normal are highly suggestive. The ISTH scoring system, which combines these values, is the most validated diagnostic tool.

January 12, 2026 AT 08:32

So let me get this straight - we’re giving people cancer drugs that come with a ‘silent death’ clause and no warning label? And the FDA only caught on after 23% more people started bleeding out? Brilliant. Just brilliant. I’m sure the pharmaceutical reps had a toast at their quarterly meeting: ‘Cheers to another 10% profit margin and zero liability.’