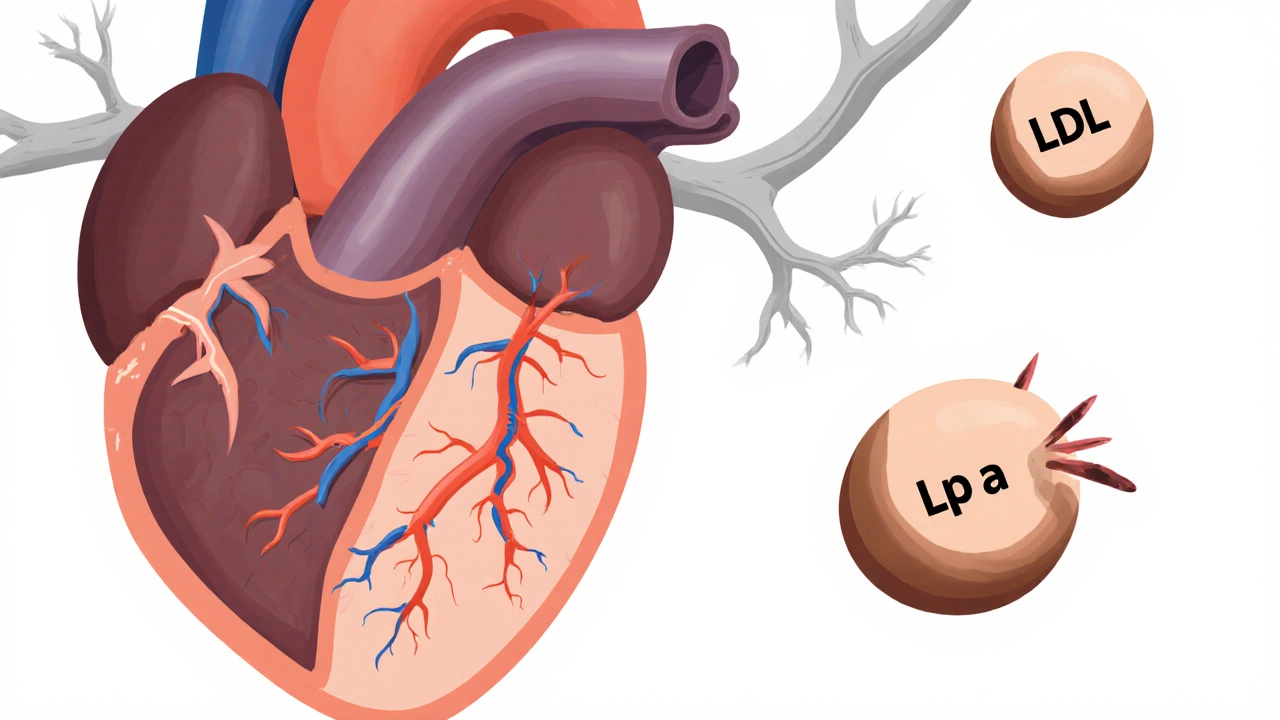

Most people know about LDL cholesterol - the "bad" kind that clogs arteries. But there’s another silent player in heart disease that doesn’t show up on routine blood tests: lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a). Unlike regular cholesterol, Lp(a) isn’t affected by diet or exercise. It’s not something you can fix with a salad or a gym session. It’s written into your genes. And if you have high levels, your risk of a heart attack or stroke could be much higher than you realize - even if your other cholesterol numbers look perfect.

What Exactly Is Lipoprotein(a)?

Lipoprotein(a), often written as Lp(a), is a type of lipoprotein particle that carries cholesterol and fat through your bloodstream. It looks a lot like LDL - the cholesterol that builds up in artery walls - but it has one extra protein attached: apolipoprotein(a). That extra piece makes it dangerous. It sticks to damaged areas in your arteries, helps form plaques, and blocks your body’s natural ability to break down blood clots. This means it doesn’t just contribute to clogged arteries - it also makes clots more likely to stick around and cause heart attacks or strokes.

It was first discovered in 1963 by a Swedish researcher, but for decades, doctors didn’t take it seriously. Today, we know better. Studies show that Lp(a) is one of the most powerful independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease - meaning it can hurt you even if you don’t smoke, aren’t overweight, and have normal blood pressure.

How Common Is High Lp(a)?

About one in five people worldwide - roughly 20% - have elevated Lp(a) levels. That makes it the most common inherited cholesterol problem you’ve never heard of. And here’s the kicker: you can’t tell if you have it without a specific blood test. Standard lipid panels don’t check for it. If your doctor doesn’t order it, you’ll never know.

Levels above 50 mg/dL (or 105 nmol/L) are considered high risk. For some people, levels climb above 90 mg/dL (190 nmol/L), which puts their risk on par with someone who has familial hypercholesterolemia - a well-known genetic condition that causes extremely high cholesterol from birth. In fact, people with Lp(a) levels between 130 and 391 mg/dL have the same heart disease risk as those with familial hypercholesterolemia.

Why Is Lp(a) So Hard to Manage?

Here’s the frustrating part: lifestyle changes barely touch Lp(a). Eating less saturated fat, losing weight, or running marathons won’t lower your levels. Statins - the most common cholesterol drugs - don’t help much. In fact, they might even nudge Lp(a) up a little in some people. Niacin can reduce it by 20-30%, but it causes flushing, liver issues, and doesn’t clearly prevent heart attacks.

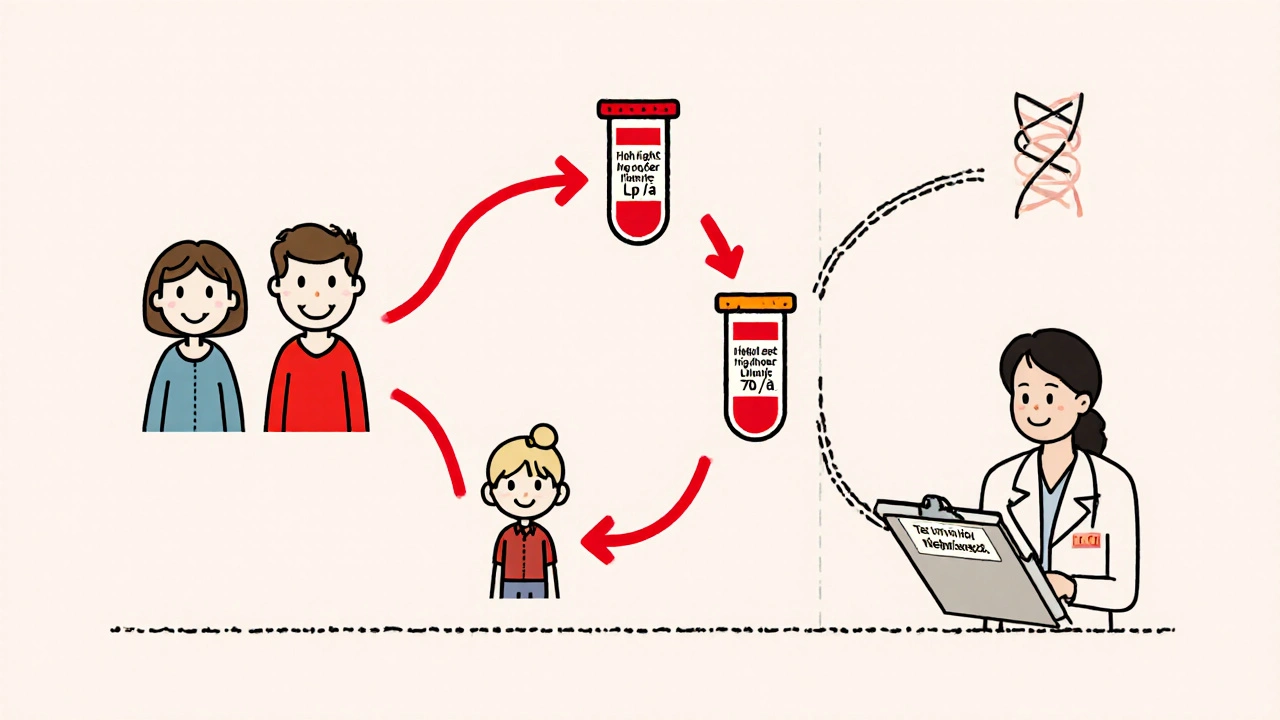

That’s because Lp(a) levels are 70% to 90% determined by your genes - specifically, variations in the LPA gene. This gene controls how many copies of a repeating structure (called kringle IV) are in the apolipoprotein(a) protein. The more repeats you have, the lower your Lp(a) level. Fewer repeats? Higher levels. It’s like inheriting a height gene - you don’t choose it. You just have it.

This genetic link explains why Lp(a) runs in families. If one parent has high Lp(a), each child has a 50% chance of getting it. That’s why doctors now recommend testing anyone with a family history of early heart disease, stroke, or aortic valve problems.

Who Should Get Tested?

Testing for Lp(a) is simple - it’s just a blood test. But it doesn’t happen unless someone asks for it. Here’s who should definitely get checked:

- Anyone with a family history of early heart disease (before age 55 in men, before 65 in women)

- People diagnosed with familial hypercholesterolemia

- Those who’ve had a heart attack, stroke, or peripheral artery disease with no obvious cause

- People with aortic valve stenosis - especially if they’re under 70

- Anyone with high LDL despite being on statins

Some experts, including cardiologists from the University of Colorado and UC Davis Health, now recommend that all adults get tested once in their lifetime. Why? Because knowing your Lp(a) level changes how you manage your overall heart risk. If you have high Lp(a), you need to be extra strict about controlling everything else - blood pressure, diabetes, smoking, and LDL cholesterol.

Population Differences Matter

Lp(a) levels vary widely across ethnic groups. Black individuals tend to have significantly higher levels than white, Hispanic, or Asian populations. Women often see their levels rise after menopause, likely because estrogen - which helps keep Lp(a) low - drops. That’s one reason why heart disease risk spikes for women in their 50s and beyond.

But here’s the key point: no matter your race, gender, or age, higher Lp(a) means higher risk. A level of 70 mg/dL is dangerous whether you’re a 40-year-old Black man or a 65-year-old white woman. The risk doesn’t care about your background - it only cares about the number.

What Does High Lp(a) Actually Do to Your Body?

High Lp(a) doesn’t just raise your cholesterol. It attacks your arteries in three ways:

- Builds plaque - Like LDL, it deposits cholesterol in artery walls, leading to atherosclerosis.

- Triggers inflammation - It makes existing plaques more unstable and likely to rupture, causing heart attacks.

- Blocks clot breakdown - The kringle structures in Lp(a) bind to fibrin, the protein that forms blood clots, and stop your body from dissolving them. This means clots last longer, increasing stroke and heart attack risk.

This is why people with high Lp(a) are more likely to have heart attacks at younger ages, even if they’re otherwise healthy. It’s also why aortic valve stenosis - a condition where the heart’s main valve narrows - is strongly linked to Lp(a). The same sticky particles that clog arteries also build up on the valve, hardening it over time.

Current Treatment Options - And the Hope on the Horizon

Right now, there’s no approved drug that directly targets Lp(a). But that’s about to change.

For now, the strategy is damage control:

- Keep your LDL cholesterol as low as possible - often below 55 mg/dL if you have high Lp(a)

- Control blood pressure

- Don’t smoke

- Manage diabetes if you have it

- Consider low-dose aspirin if your doctor says it’s right for you

There’s one promising drug in the pipeline: pelacarsen. It’s an antisense oligonucleotide - a type of genetic therapy that tells your liver to stop making apolipoprotein(a). In phase 2 trials, it lowered Lp(a) by up to 80%. The big phase 3 trial - called the Lp(a) HORIZON Outcomes Trial - is testing whether lowering Lp(a) with pelacarsen actually prevents heart attacks and strokes. Results are expected in 2025.

If the trial works, pelacarsen could become the first treatment specifically approved to target Lp(a). That would be a game-changer for millions of people who’ve been told, "There’s nothing you can do."

What You Can Do Today

If you haven’t been tested for Lp(a), ask your doctor. It’s a simple blood test - no fasting required. If your level is high, don’t panic. You’re not doomed. You’re just at higher risk - and that means you have more control over the rest.

Focus on what you can control:

- Get your LDL cholesterol down - statins, ezetimibe, or PCSK9 inhibitors may be needed

- Keep your blood pressure under 120/80

- Avoid smoking and vaping

- Exercise regularly - it won’t lower Lp(a), but it helps your arteries stay flexible

- Eat a heart-healthy diet: vegetables, whole grains, nuts, fish, and lean protein

- Talk to your doctor about aspirin - it may help reduce clot risk

And if you have a family history of early heart disease, get your kids tested when they’re adults. Early detection saves lives.

Final Thought: Knowledge Is Power

Lp(a) isn’t your fault. You didn’t cause it. You can’t fix it with willpower. But now you know it exists - and that knowledge changes everything. You can’t change your genes, but you can change your plan. And in heart disease, a smarter plan can mean the difference between a healthy life and a life-altering event.

Ask for the test. Know your number. Control what you can. And wait for the next breakthrough - because it’s coming.

Is lipoprotein(a) the same as LDL cholesterol?

No. Lp(a) is a separate lipoprotein particle that includes an LDL-like core but has an extra protein called apolipoprotein(a) attached. While both carry cholesterol, Lp(a) is more dangerous because it promotes plaque buildup, inflammation, and blood clots. Standard cholesterol tests don’t measure Lp(a), so you need a specific test to find out your level.

Can diet and exercise lower lipoprotein(a)?

Not significantly. Unlike LDL cholesterol, Lp(a) levels are mostly controlled by genetics - over 90% determined by your LPA gene. While healthy eating and regular exercise are still important for overall heart health, they won’t reduce your Lp(a) level. The best strategy is to aggressively manage other risk factors like LDL cholesterol and blood pressure.

How do I know if I have high lipoprotein(a)?

You need a specific blood test. Standard lipid panels don’t include Lp(a). Ask your doctor for an Lp(a) test if you have a family history of early heart disease, stroke, or aortic stenosis - or if you’ve had a cardiovascular event with no clear cause. Levels above 50 mg/dL (or 105 nmol/L) are considered high risk.

Is lipoprotein(a) testing covered by insurance?

Coverage varies. Many insurers will pay for the test if you have a strong family history of early heart disease, personal history of cardiovascular events, or familial hypercholesterolemia. If you don’t meet those criteria, you may need to pay out-of-pocket - the test typically costs between $50 and $150. It’s worth it if you’re at risk.

Will new drugs for lipoprotein(a) be available soon?

Yes. The drug pelacarsen, which reduces Lp(a) by up to 80%, is currently in phase 3 clinical trials. Results are expected in 2025. If successful, it could become the first FDA-approved treatment specifically designed to lower Lp(a) and reduce heart attack and stroke risk in high-risk patients.

If I have high lipoprotein(a), should my family get tested?

Yes. Since Lp(a) is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, each of your children has a 50% chance of inheriting your high level. Siblings and parents should also consider testing. Early detection allows for better long-term heart disease prevention - especially since symptoms often don’t appear until damage is already done.

November 14, 2025 AT 11:22

Man I had no idea Lp(a) was such a silent killer

My dad had a heart attack at 48 and no one ever tested him for this

Wish I knew sooner