When a generic drug hits the market, it’s not enough for it to contain the same active ingredient as the brand-name version. It has to perform the same way in the body. That’s where bioequivalence (BE) testing comes in. For decades, regulators relied on two simple metrics: Cmax (the highest concentration in the blood) and AUC (the total drug exposure over time). But for complex drug formulations-like extended-release painkillers or abuse-deterrent opioids-those numbers weren’t telling the whole story. That’s where partial AUC, or pAUC, stepped in.

Why Traditional Metrics Fall Short

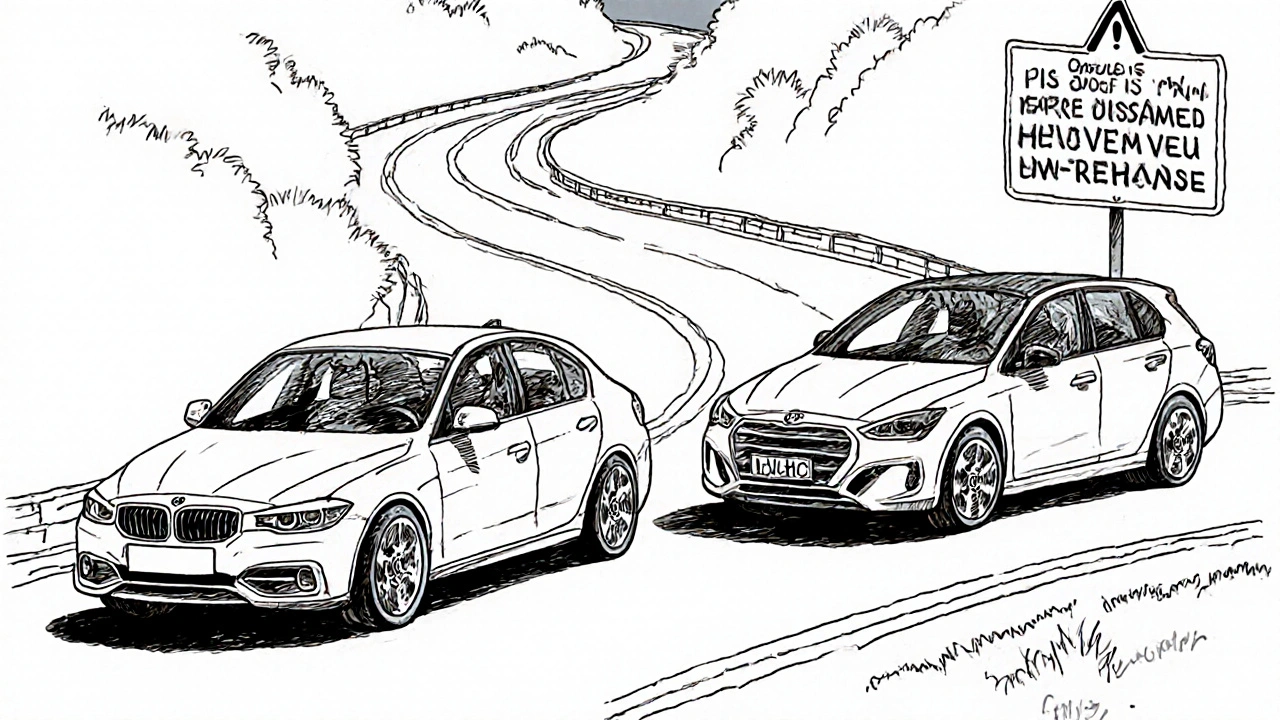

Think of a drug’s journey through your body like a car trip. Cmax is the top speed you hit. AUC is the total distance traveled. But what if two cars reach the same total distance and top speed, but one accelerates too slowly, and the other spikes too fast? They might both get you to the destination, but one could cause a crash. That’s the problem with traditional BE metrics for advanced formulations. For example, a generic version of an extended-release opioid might have the same Cmax and total AUC as the brand drug. But if it releases the drug too slowly in the first two hours, patients might not get enough pain relief early on. Or if it releases too much too fast, it could increase abuse risk. Traditional tests wouldn’t catch that. The FDA and EMA started seeing cases where generics passed standard BE tests but failed in real-world use. That’s when regulators realized they needed a more precise tool.What Is Partial AUC (pAUC)?

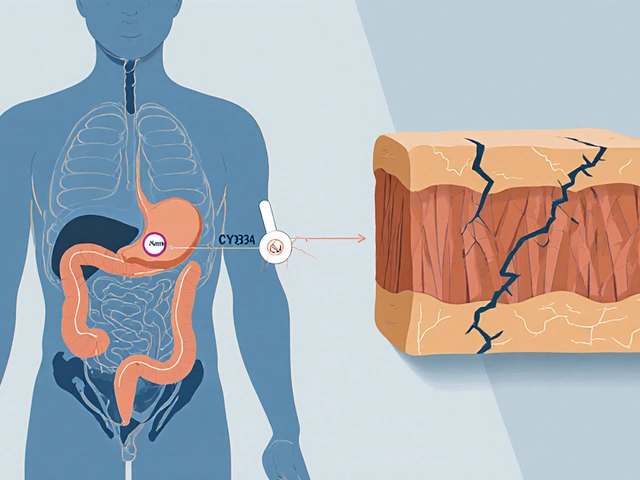

Partial AUC is a pharmacokinetic measurement that looks at drug exposure only during a specific, clinically meaningful time window-not the entire curve. Instead of measuring total exposure from 0 to 24 hours, you might focus on 0 to 2 hours, or 0 to the time when the reference drug reaches its peak concentration (Tmax). This lets you zoom in on the part of the curve that matters most for safety or effectiveness. The FDA officially started recommending pAUC in 2013, after a series of cases showed that generics were slipping through the cracks. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) had already flagged the issue in its 2013 draft guidance, especially for prolonged-release products. By 2018, the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) made pAUC a priority across all drug divisions. Today, over 127 specific drug products require pAUC analysis in their bioequivalence submissions.How Is pAUC Calculated?

There’s no single formula for pAUC. The time window depends on the drug and its intended use. The FDA outlines three common approaches:- Time from dosing until the reference product reaches its peak concentration (Tmax)

- A time interval where drug concentration exceeds 50% of Cmax

- A fixed window where concentrations are clinically relevant-for example, the first 2 hours for fast-acting drugs

Statistical analysis often uses the Bailer-Satterthwaite-Fieller method to calculate confidence intervals, especially in studies with destructive sampling (where each subject only provides a few blood samples instead of a full profile). This method helps reduce uncertainty when data is sparse.

Where Is pAUC Most Important?

pAUC isn’t needed for every drug. It’s reserved for complex formulations where timing matters:- Extended-release opioids: Early exposure must match the brand to prevent withdrawal or abuse.

- Abuse-deterrent formulations: If a generic releases the drug too quickly when crushed, it defeats the safety design.

- Mixed-mode products: Combining immediate- and extended-release components requires both rapid onset and sustained effect.

- CNS drugs: Drugs for epilepsy, Parkinson’s, or depression need consistent early exposure to avoid breakthrough symptoms.

According to FDA data from 2022, 68% of new submissions for central nervous system drugs required pAUC. For pain management, it was 62%. Cardiovascular drugs followed at 45%. Meanwhile, simple immediate-release tablets rarely need it.

The Real-World Impact

The stakes are high. In one case presented at the 2021 AAPS meeting, a generic opioid failed to show bioequivalence using traditional metrics-but pAUC revealed a 22% difference in early drug exposure. That gap could mean patients didn’t get enough pain relief in the first hour. The product was pulled before it reached the market. On the flip side, companies have paid a price to comply. A senior biostatistician at Teva reported that adding pAUC to one extended-release opioid study increased the sample size from 36 to 50 subjects. That added $350,000 to development costs. Why? Because pAUC is more sensitive-and more variable. Smaller differences matter more, so you need more data to be sure.Industry surveys show that 63% of generic drug developers now need extra statistical help for pAUC analysis, compared to just 22% for traditional BE tests. And 17 ANDA submissions were rejected in 2022 solely due to incorrect pAUC time window selection. That’s 8.5% of all BE-related deficiencies that year.

Challenges and Controversies

The science behind pAUC is solid. But the implementation? Messy. One big problem: inconsistency. The FDA’s product-specific guidances (over 2,000 as of 2023) recommend pAUC for 15% of them-but only 42% clearly explain how to pick the time interval. Some say use Tmax. Others say use 50% of Cmax. Some use fixed hours. Generic manufacturers are left guessing, leading to delays and rejected applications. Dr. Donald Mager from the University at Buffalo pointed out in 2020 that pAUC can require sample sizes 25-40% larger than traditional methods. That means more participants, more blood draws, higher costs-and slower approval times. And global harmonization? Still lacking. The EMA, FDA, and Health Canada all have slightly different approaches. The IQ Consortium estimates this inconsistency adds 12-18 months to global generic drug development.

What’s Next for pAUC?

The trend is clear: pAUC is here to stay. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance added 41 more drugs requiring pAUC, bringing the total to 127. Evaluate Pharma predicts that by 2027, 55% of all new generic approvals will need pAUC analysis-up from 35% in 2022. To reduce confusion, the FDA launched a pilot program in early 2023 using machine learning to automatically suggest optimal time intervals based on historical reference product data. Early results show promise. CROs like Algorithme Pharma are already building proprietary pAUC tools, and 87% of bioequivalence specialist job postings now list pAUC expertise as required.How to Get Started

If you’re working in generic drug development, here’s how to approach pAUC:- Check the product-specific guidance-if it’s listed, pAUC is mandatory.

- Identify the clinically relevant window-what time period affects safety or efficacy? Use pharmacodynamic data if available.

- Use reference product Tmax as a starting point if no PD data exists.

- Run pilot studies to understand variability before designing the full BE trial.

- Partner with a biostatistician experienced in pAUC-don’t try to wing it.

Training takes time. Most biostatisticians need 3-6 months to become proficient. Tools like Phoenix WinNonlin and NONMEM are essential. And don’t assume your old BE protocols will work. pAUC changes the game.

Final Thoughts

Partial AUC isn’t just another statistic. It’s a shift in how we think about bioequivalence. Instead of asking, “Did the drug get absorbed?” we’re now asking, “Did it get absorbed at the right time, in the right way?” For patients, this means safer, more effective generics. For developers, it means higher costs and more complexity. But the science is clear: for complex drugs, traditional metrics are no longer enough. pAUC fills the gap-and it’s becoming the new standard.Is partial AUC required for all generic drugs?

No. Partial AUC is only required for specific complex drug formulations, such as extended-release opioids, abuse-deterrent products, and mixed-mode release systems. Most simple immediate-release generics still only need Cmax and total AUC. Always check the FDA’s product-specific guidance for the drug you’re developing.

How does pAUC differ from total AUC?

Total AUC measures the entire drug exposure from time zero to the last measurable concentration-usually 24 hours or more. Partial AUC looks only at a defined window, like the first 2 hours or until the reference product peaks. This lets regulators focus on critical phases of absorption that impact safety or effectiveness, rather than overall exposure.

Why is pAUC more variable than Cmax or AUC?

Because pAUC focuses on a smaller, more sensitive part of the concentration-time curve-often during the absorption phase where individual differences in gastric emptying, enzyme activity, or formulation dissolution are most pronounced. Small variations in these factors can cause larger fluctuations in pAUC values, requiring larger study sizes to achieve statistical power.

What happens if a generic drug fails pAUC but passes Cmax and AUC?

It fails bioequivalence. The FDA and EMA require all specified metrics to meet the 80-125% confidence interval. Passing Cmax and AUC isn’t enough if pAUC falls outside that range. This has led to rejected applications and delayed approvals, especially when the time window wasn’t properly justified.

Can I use a fixed time window for pAUC, like 0-2 hours?

Sometimes, but only if supported by clinical or pharmacodynamic data. The FDA recommends that the time window be tied to a clinically relevant effect-like the time when pain relief begins or when abuse potential peaks. Using a fixed window without justification can lead to rejection. Reference product Tmax is often the safest starting point.

How do I know which time interval to choose for my drug?

Start by reviewing the FDA’s product-specific guidance for your drug. If it’s not specified, use the reference product’s Tmax as your cutoff. If you have pharmacodynamic data (like time to pain relief or seizure control), align the window with that. Pilot studies can help determine variability and refine your choice before the full BE trial.

Is pAUC used outside the U.S. and Europe?

Yes, but inconsistently. Health Canada, Japan’s PMDA, and Australia’s TGA have adopted pAUC for some products, but their guidelines vary. This lack of global alignment is a major challenge for multinational generic manufacturers, often adding over a year to development timelines. Harmonization efforts are ongoing through organizations like the IQ Consortium.

November 18, 2025 AT 20:17

so uhm... i think the fda just made this up to keep big pharma rich? like why do we need to measure the first 2 hours? sounds like a scam to make generics cost more. my cousin took a generic oxycodone and it worked fine, so... idk man. maybe they're just scared of people getting high too fast? 🤔