Alzheimer's vs DAT Comparison Tool

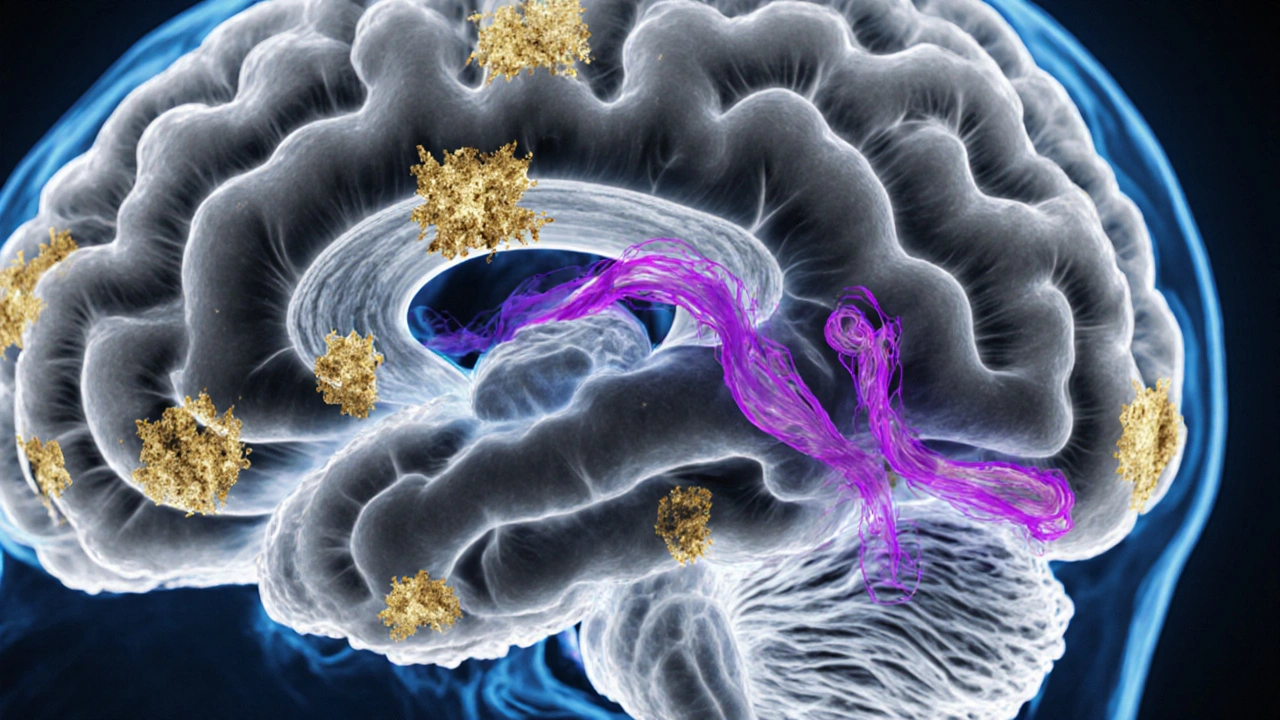

Alzheimer’s disease is a specific brain disease defined by its pathology (amyloid plaques and tau tangles).

Dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (DAT) is a clinical diagnosis based on symptoms and supportive tests, indicating probable Alzheimer’s disease.

Select a question above to see detailed information about Alzheimer's disease vs Dementia of the Alzheimer's Type.

| Feature | Alzheimer's Disease | Dementia of the Alzheimer's Type |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Confirmed by brain autopsy or validated biomarkers | Probable AD based on cognitive profile and supporting evidence |

| Onset Age | 65+ (early-onset rare) | Typically 65+ |

| Pathology | Definitive amyloid plaques and tau tangles | Supportive evidence of amyloid and tau changes |

| Diagnosis | Autopsy or biomarker confirmation | Clinical assessment + supportive tests |

| Prognosis | Progressive decline | Similar progression pattern |

Key Takeaways

- Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a specific brain disease; Dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (DAT) describes the clinical picture caused by AD.

- Both share amyloid plaques and tau tangles, but DAT is diagnosed by symptoms and tests, not by pathology alone.

- Onset, progression, and treatment plans are similar, yet the terminology matters for doctors, caregivers, and insurance.

- Biomarkers, neuroimaging, and cognitive testing help separate DAT from other dementias.

- Early detection improves management, regardless of the label you use.

People often hear "Alzheimer’s" and "Alzheimer’s‑type dementia" used interchangeably, which creates confusion at doctor visits and support groups. This article strips away the jargon, shows where the two terms overlap, and points out the subtle but important differences.

What is Alzheimer’s disease?

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by memory loss, cognitive decline, and behavioral changes. The disease starts deep inside the brain, where abnormal proteins-amyloid‑beta and tau-accumulate and slowly damage neurons. Over years, this damage spreads from the hippocampus (the memory hub) to the cortex, affecting language, judgment, and eventually basic daily functions.

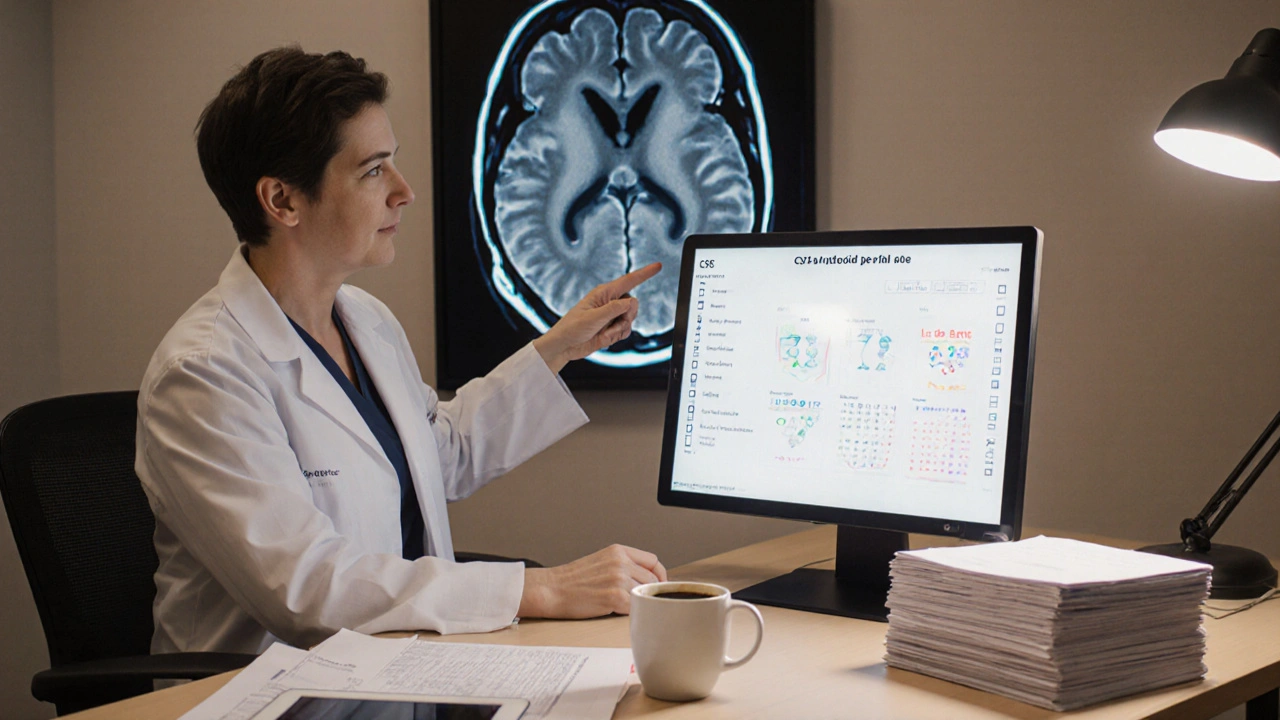

AD is defined by its pathology. Autopsy studies show the classic hallmarks: extracellular amyloid plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles. In living patients, doctors rely on biomarkers (e.g., CSF amyloid‑beta42, PET scans) to infer the same changes.

What is Dementia of the Alzheimer’s type?

Dementia of the Alzheimer’s type, often abbreviated DAT, is a clinical diagnosis. It means the patient shows the pattern of cognitive decline that most frequently results from Alzheimer’s disease pathology. In other words, DAT describes *what the patient experiences*-memory problems, disorientation, and loss of executive function-while assuming the underlying cause is AD.

Why use a different label? Because at the time of diagnosis doctors may not have pathological proof. The term lets clinicians communicate a high probability that AD is the culprit, while still allowing for re‑classification if later tests point elsewhere.

Core pathological differences

From a strictly biological standpoint, there is no separate "DAT brain"; the same plaques and tangles seen in AD show up in DAT patients. The distinction lies in certainty:

- Alzheimer’s disease: confirmed by pathology or validated biomarkers.

- Dementia of the Alzheimer’s type: probable AD based on clinical patterns and supportive tests.

Other dementias-vascular, Lewy body, frontotemporal-share some symptoms but differ in the dominant protein aggregates (e.g., alpha‑synuclein in Lewy body). Recognizing DAT helps exclude those alternatives.

Clinical presentation and diagnostic criteria

Both AD and DAT follow a similar symptom trajectory, but the diagnostic process adds layers:

| Feature | Alzheimer’s disease (pathological) | Dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (clinical) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary definition | Confirmed by brain autopsy or validated biomarkers | Probable AD based on cognitive profile and supporting evidence |

| Typical onset age | 65+ (early‑onset <60 is <5% of cases) | Same age distribution as AD |

| Core pathology | Amyloid plaques + neurofibrillary tau tangles | Assumed same pathology, but not directly visualized |

| Diagnostic tools | CSF amyloid‑beta, PET amyloid/tau imaging, genetic testing (APP, PSEN1/2) | Neuropsychological battery, MRI for atrophy, optional CSF/PET if uncertain |

| Diagnostic criteria | NIA‑AA (2023) pathology‑based criteria | NIA‑AA (2023) clinical‑probable AD criteria |

| Progression speed | Average 8-10 years from mild to severe | Similar trajectory; variability depends on comorbidities |

| Treatment focus | Disease‑modifying agents targeting amyloid/tau (e.g., lecanemab) | Symptomatic meds (acetylcholinesterase inhibitors) + same disease‑modifiers when eligible |

The table shows that the "difference" is largely about *how sure we are* of the underlying biology. In everyday practice, doctors use DAT when the full suite of biomarkers isn’t available, which is still the case for many health systems.

Treatment and management implications

Whether a patient is labeled AD or DAT, the care plan overlaps heavily:

- Cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine) improve cognition modestly in mild‑to‑moderate stages.

- NMDA‑antagonist (memantine) helps moderate‑to‑severe disease.

- Disease‑modifying therapies such as lecanemab or donanemab are approved for patients with confirmed amyloid pathology. When only DAT is diagnosed, physicians may still prescribe these drugs if insurance or trial criteria allow biomarker confirmation.

- Non‑pharmacologic support-exercise, cognitive stimulation, caregiver education-works regardless of the label.

One practical difference: insurance companies often require a biomarker‑confirmed AD diagnosis for reimbursement of expensive anti‑amyloid antibodies. In those cases, clinicians may order a PET scan or lumbar puncture to upgrade DAT to AD on the paperwork.

Common misconceptions

Misconception 1: DAT is a milder form of AD. It isn’t “milder”; it’s simply a diagnostic shorthand used before pathology is proven.

Misconception 2: If you have DAT, you can’t get disease‑modifying drugs. Many providers arrange biomarker testing to meet eligibility, so the label doesn’t block treatment.

Misconception 3: Only memory loss matters. Early AD/DAT often starts with subtle changes in spatial navigation, planning, or mood. Recognizing these signs speeds up evaluation.

Next steps for patients and caregivers

- Schedule a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment if memory issues appear.

- Ask your neurologist about biomarker testing (CSF or PET) if you’re considering anti‑amyloid therapy.

- Enroll in local support groups; many organizations use the term "Alzheimer’s‑type dementia" and can offer resources.

- Plan for legal and financial matters early-power of attorney, advance directives, and insurance coverage.

- Stay active: regular aerobic exercise, balanced diet, and social engagement can slow decline.

Understanding the terminology empowers you to ask the right questions and navigate the healthcare system more confidently.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Dementia of the Alzheimer’s type the same as Alzheimer’s disease?

They describe the same underlying brain changes, but AD is a pathology‑based label while DAT is a clinical diagnosis used when definitive tests are not yet done.

Can I get amyloid‑targeting drugs with a DAT diagnosis?

Often insurers require biomarker confirmation. Many doctors order a PET scan or CSF test to upgrade the diagnosis, making the patient eligible for drugs like lecanemab.

What tests differentiate DAT from other dementias?

Neuropsychological batteries that assess memory vs. visuospatial vs. executive function, MRI to look for vascular changes, and, when needed, CSF or PET scans for amyloid/tau clarify the cause.

How fast does DAT progress compared to AD?

Progression rates are similar because they stem from the same disease process. Average decline from mild to severe stages spans 8-10 years, though individual variation is wide.

Are lifestyle changes useful for DAT?

Yes. Exercise, a Mediterranean‑style diet, cognitive training, and good sleep can modestly delay symptom worsening, regardless of the label.

October 10, 2025 AT 20:30

First, thank you for tackling a topic that confuses so many patients and caregivers. The line between Alzheimer’s disease and Dementia of the Alzheimer’s type is more than just semantics, and understanding it can change how we approach treatment and support. Alzheimer’s disease refers to the specific pathological process-amyloid plaques and tau tangles-confirmed by autopsy or robust biomarkers. Dementia of the Alzheimer’s type, on the other hand, is the clinical label we use when we see the classic pattern of memory loss, executive dysfunction, and behavioral changes, but we don’t yet have definitive pathological proof. This distinction matters because it shapes conversations with families, eligibility for clinical trials, and insurance documentation. When a clinician says “probable AD,” they are essentially using the DAT label, acknowledging high likelihood while keeping the door open for re‑classification if new evidence emerges. Biomarker advances, such as PET amyloid scans, are narrowing that gap, turning many DAT diagnoses into confirmed AD over time. Yet, in many community settings, we still rely heavily on neuropsychological testing and brain imaging to infer the underlying disease. Knowing the difference empowers caregivers to ask the right questions about what therapies are appropriate and what prognostic information to expect. It also reduces the frustration that arises when patients hear both terms tossed around as if they mean the same thing. By separating the biological definition from the clinical syndrome, we can better align research findings with everyday practice. Moreover, recognizing DAT as a provisional label helps clinicians document uncertainty without abandoning the patient’s need for action. It’s a reminder that medicine is often a process of gathering evidence, not a single moment of certainty. Ultimately, the goal is to get patients the support they need as early as possible, regardless of the exact terminology. So keep an eye on emerging biomarker tools, but also remember that compassionate care starts with listening to the lived experience of dementia, whether we call it AD or DAT.