Creatine Adjustment Calculator

Kidney Function Adjustment Calculator

Creatine supplementation can increase serum creatinine by 10-30% without actual kidney damage. This calculator adjusts your creatinine values to estimate what they would be without creatine, helping you distinguish true kidney function from supplement effects.

How it works

Creatine typically increases serum creatinine by 10-30% depending on dosing. This calculator subtracts the supplement effect to estimate your true kidney function. For most people, this adjustment is temporary and reverses after stopping creatine.

Important Note

Always consult your doctor for interpretation of kidney function results. This calculator provides an estimate only and should not replace professional medical advice.

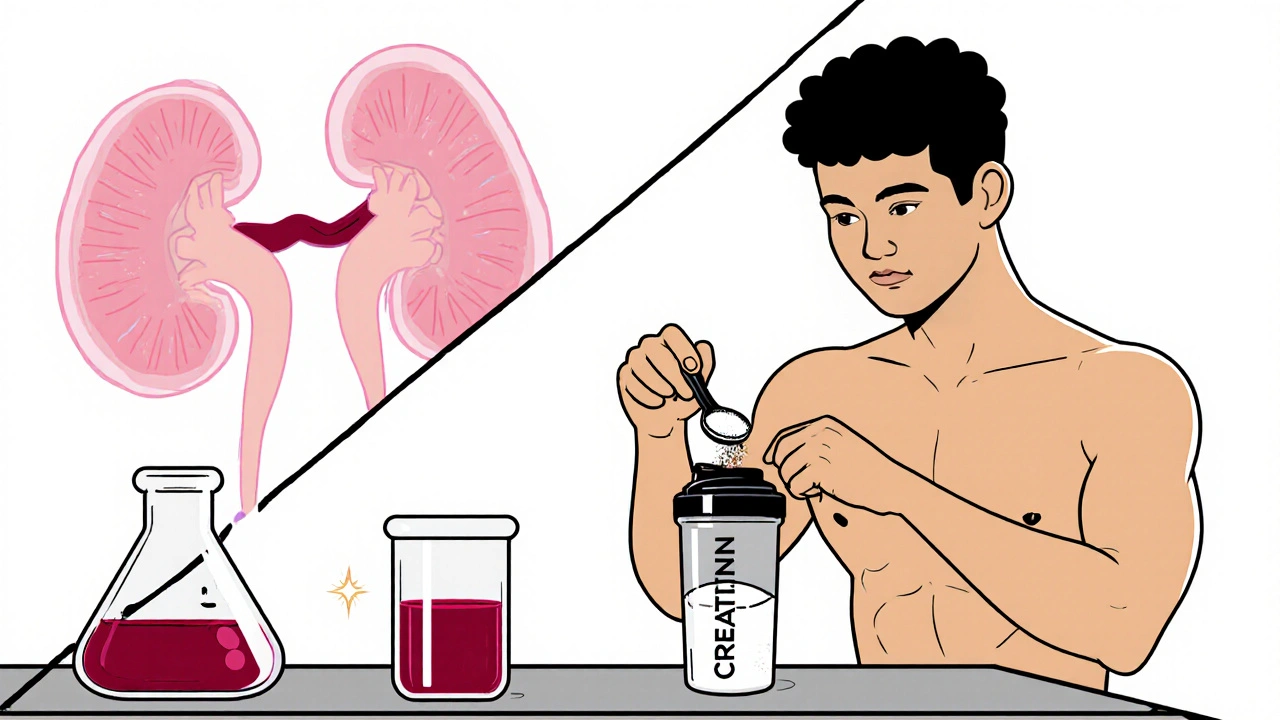

When athletes or gym‑goers start taking creatine supplementation, they often hear the word "creatinine" and wonder if their kidneys are at risk. The truth is a bit more nuanced: the supplement can raise serum creatinine without actually hurting the kidneys, but that spike can confuse doctors, especially if the person also takes kidney‑related medications. Below we untangle how creatine interacts with renal labs, which drugs matter most, and what monitoring steps keep you safe.

Why Creatine Affects Creatinine Levels

Creatine supplementation is a dietary strategy that increases the body’s store of phosphocreatine, boosting short‑burst energy for high‑intensity exercise. About 90% of ingested creatine is filtered by the kidneys, and a small portion spontaneously converts to creatinine each day. Studies such as Robinson et al. (2000) show a typical 20 g/day loading phase lifts serum creatinine by roughly 15‑25 µmol/L - a 10‑30% jump that does not reflect true glomerular filtration decline.

Creatinine vs. True Kidney Dysfunction

The kidney‑function gold standard remains the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), which laboratories calculate from serum creatinine. When creatine raises that creatinine, eGFR can appear lower, mistakenly flagging chronic kidney disease (CKD). Real CKD, however, presents a broader lab picture: elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN), proteinuria, and electrolyte shifts alongside rising creatinine.

Alternative Biomarkers That Don’t Mislead

Because creatinine is directly influenced by supplementation, clinicians turn to markers that stay steady. Cystatin C is a small protein cleared by the kidneys independent of muscle mass or creatine intake. Gualano et al. (2008) demonstrated unchanged cystatin C levels in participants taking up to 0.3 g/kg/day creatine for weeks. When cystatin C‑based equations (CKD‑EPI CysC) are used, eGFR correlates well with measured GFR even in supplement users.

Guideline‑Based Monitoring Protocol

The National Kidney Foundation (2023) recommends a simple three‑step protocol for anyone starting creatine:

- Obtain a baseline panel: serum creatinine, BUN, electrolytes, and if possible cystatin C.

- Re‑check labs after the loading phase (about one week) and again after three months of maintenance dosing.

- If creatinine rises but cystatin C and urine studies stay normal, interpret the change as a supplement effect, not renal injury.

When cystatin C testing isn’t available, a 24‑hour urinary creatinine clearance offers a reliable alternative, as the total creatinine excreted remains unchanged in healthy users (Eijnde et al., 2003).

Medication Interactions That Heighten Risk

Some drugs already stress the kidneys, and adding creatine can muddy the clinical picture. The most common culprits include:

- ACE inhibitors - lower glomerular pressure, making eGFR more sensitive to creatinine fluctuations.

- NSAIDs - reduce renal blood flow, increasing the chance of true AKI if dehydration or over‑training occurs.

- Diuretics - can cause electrolyte imbalances that overlap with signs of kidney stress.

Patients on any of these should discuss creatine use with their physician, who might opt for a lower maintenance dose (e.g., 2 g/day) and more frequent monitoring.

Real‑World Cases: When Creatine Masked or Mimicked Kidney Issues

On Reddit’s r/kidneydisease forum (Jan 2023), user “FitMedStudent” shared a story of being labeled stage 2 CKD after a routine check while on 5 g/day creatine. After stopping the supplement, his eGFR rose from 78 mL/min/1.73 m² to 95 mL/min/1.73 m² within two weeks - a classic false‑positive scenario.

Conversely, a 2011 case report in the Clinical Kidney Journal described a rare instance of acute tubular necrosis in a healthy individual taking a standard 3 g/day dose without any nephrotoxic drugs. While noteworthy, that single outlier sits against a backdrop of >500 participants across multiple trials showing no renal impairment.

Practical Checklist for Athletes and Clinicians

Below is a straightforward cheat‑sheet you can print or save on your phone.

- Ask your doctor specifically about creatine supplementation during any blood work.

- Document the exact dose and timing (loading vs. maintenance).

- Insist on a baseline cystatin C or 24‑hour urine test if you’re on ACE inhibitors, NSAIDs, or have CKD.

- Re‑test after the first week of loading and every three months thereafter.

- If creatinine rises >20% but cystatin C is stable, note “creatine effect” in your chart and avoid unnecessary referrals.

- Stay hydrated, especially when training hard and taking NSAIDs.

Future Directions: Adjusting eGFR for Creatine Users

Researchers at the University of Toronto presented preliminary data (ASN Kidney Week 2023) suggesting a simple multiplier - 0.9 - applied to creatinine‑based eGFR in regular creatine users. If validated, labs could automatically correct for the supplement’s impact, removing most of the confusion. The National Kidney Foundation is expected to incorporate such adjustments in its Q4 2024 guideline update.

Bottom Line

Creatine remains one of the safest and most effective performance aids for healthy adults. The main caution is its interference with creatinine‑based kidney tests, especially when patients are also on drugs like ACE inhibitors or NSAIDs. By establishing a baseline, using alternative biomarkers, and keeping an eye on medication interactions, you can continue to reap creatine’s benefits without unnecessary renal scares.

| Marker | Influence by Creatine | Reliability for GFR | Typical Clinical Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum Creatinine | ↑10‑30% with standard dosing | Variable - may overestimate CKD | Standard eGFR calculation (creatinine‑based) |

| Cystatin C | No measurable change | High - stable across muscle mass | CysC‑based eGFR (CKD‑EPI CysC) |

| 24‑hr Urinary Creatinine Clearance | Unaffected (total excretion stable) | High - reflects true filtration | Alternative when CysC unavailable |

Can creatine cause permanent kidney damage?

Large, well‑controlled trials involving hundreds of participants show no lasting decline in measured GFR from standard creatine doses. Isolated case reports exist, but they represent rare outliers rather than a causal pattern.

Should I stop creatine if my doctor says my creatinine is high?

First, ask whether alternative markers (cystatin C or urine clearance) were checked. If those are normal, the rise is likely from the supplement and you can continue with adjusted monitoring. If other kidney signs appear, pause the supplement and investigate further.

Do ACE inhibitors make creatine riskier?

ACE inhibitors lower glomerular pressure, so any true kidney stress can be amplified. While they don’t cause creatine‑induced creatinine spikes to become harmful on their own, combining them warrants closer lab follow‑up (e.g., every 4‑6 weeks).

Is cystatin C testing covered by insurance?

Coverage varies by country and plan. In Australia, many Medicare‑eligible labs include cystatin C as part of a renal panel for high‑risk patients; check with your provider.

How long should I wait after stopping creatine before retesting?

Serum creatinine typically normalizes within 1‑2 weeks after discontinuation, given its 3‑4 hour plasma half‑life. Re‑test after 10‑14 days to see the true baseline.

October 26, 2025 AT 14:52

In the grand theater of sports nutrition, creatine proudly takes center stage while serum creatinine claps politely in the background, a classic case of correlation without causation. The peer‑reviewed literature demonstrates that a standard loading phase will inflate creatinine by roughly 10–30% without any measurable decline in glomerular filtration rate, a nuance that most clinicians miss as if they were reading a comic strip. Hence, the proper clinical response is not to outlaw creatine but to adjust the interpretation of creatinine‑based eGFR calculations, perhaps by employing cystatin C or a creatinine correction factor. Of course, this assumes the patient isn’t simultaneously sipping NSAIDs or ACE inhibitors, which could transform a harmless spike into a diagnostic nightmare. In short, the supplement itself is innocent; the real villain is the uninformed lab report.