When a brand-name drug hits the market, its patent clock starts ticking. But for many top-selling medicines, the real battle doesn’t end when that first patent expires-it’s just getting started. Behind the scenes, pharmaceutical companies are filing secondary patents to keep generics off the shelf, sometimes for more than a decade after the original protection runs out. These aren’t new drugs. They’re tweaks. New forms. Different doses. New uses. And they’re the main reason why some medications cost hundreds or even thousands of dollars longer than they should.

What Exactly Are Secondary Patents?

A primary patent protects the active chemical ingredient-the molecule itself. That’s the core invention. Secondary patents cover everything else: how the drug is made, how it’s delivered, or how it’s used. Think of it like buying a car. The primary patent is the engine design. A secondary patent could be the special suspension, the color, or even the fact that it’s now approved to drive on sand dunes instead of just highways. These aren’t minor details. They’re legal tools. The most common types include:- Polymorphs: Different crystal structures of the same drug. A slight change in how molecules pack together can get a new patent.

- Formulations: Sustained-release pills, liquid versions, patches, or inhalers. AstraZeneca’s switch from Prilosec (omeprazole) to Nexium (esomeprazole)-a single enantiomer version-extended exclusivity by nearly 8 years.

- Method-of-use: Patents on treating a new disease. Thalidomide was originally a sleep aid. Later, it got patents for leprosy and then multiple myeloma.

- Combinations: Mixing two drugs into one pill. This is common in HIV and hypertension treatments.

- Salts and esters: Chemical tweaks that improve absorption or stability.

According to Drug Patent Watch, a single drug can be covered by over 100 patents. Most of these aren’t listed in the FDA’s Orange Book-only the ones tied to delivery or use are. The rest? They’re hidden in plain sight, waiting to be used as legal weapons against generic challengers.

How They Delay Generic Competition

Generic manufacturers can’t launch until all listed patents expire-or until they successfully challenge them in court. But here’s the catch: many secondary patents are filed years before the primary one expires. Companies plan this like a chess game.- Five to seven years before the main patent runs out, R&D teams start working on new formulations.

- Three to four years out, they file the patent.

- One to two years before expiration, they launch the new version-often with marketing campaigns pushing it as "better," "safer," or "more convenient."

This tactic, called "product hopping," confuses doctors and patients. Why switch to a more expensive version if the old one works fine? But once patients are on the new formulation, insurers often stop covering the old one. The generic version of the original drug can’t enter the market because the new version is still under patent.

Result? Generic entry is delayed by an average of 2.3 years longer than it would be without secondary patents, according to a 2019 Health Affairs study. For drugs like Humira, which had 264 secondary patents, the delay stretched to over 7 years. The drug cost $20 billion a year in the U.S. during that time-money that could’ve gone to cheaper generics.

The Cost to Patients and Healthcare Systems

The financial impact is massive. Evaluate Pharma found that 58% of a blockbuster drug’s lifetime revenue comes during its secondary patent period. For companies, that’s billions. For patients, it’s unaffordable co-pays. For insurers, it’s ballooning costs.Pharmacy benefit managers like Express Scripts report that secondary patents increase their annual spending by 8.3%. Generic manufacturers say legal battles over these patents cost $15-20 million per drug-and that’s just to get to court. Only 38% of those challenges succeed.

And it’s not just about money. A 2016 Harvard study found that only 12% of secondary patents led to clinically meaningful improvements. Most were minor changes: a pill that dissolves faster, a slightly different dose schedule, or a color change. Yet they still block competition.

Doctors notice it too. A 2022 Medscape survey showed that many physicians feel pressured by pharmaceutical reps to switch patients to newer versions right before generics become available. "It’s not about what’s best for the patient," one California-based doctor said. "It’s about what’s best for the company’s bottom line."

Global Differences: Where It Works and Where It Doesn’t

Not every country lets pharmaceutical companies play this game the same way.In the U.S., the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created the framework that made secondary patents possible. It gave brand-name companies extra protection in exchange for faster generic approval. But it also opened the door for patent thickets.

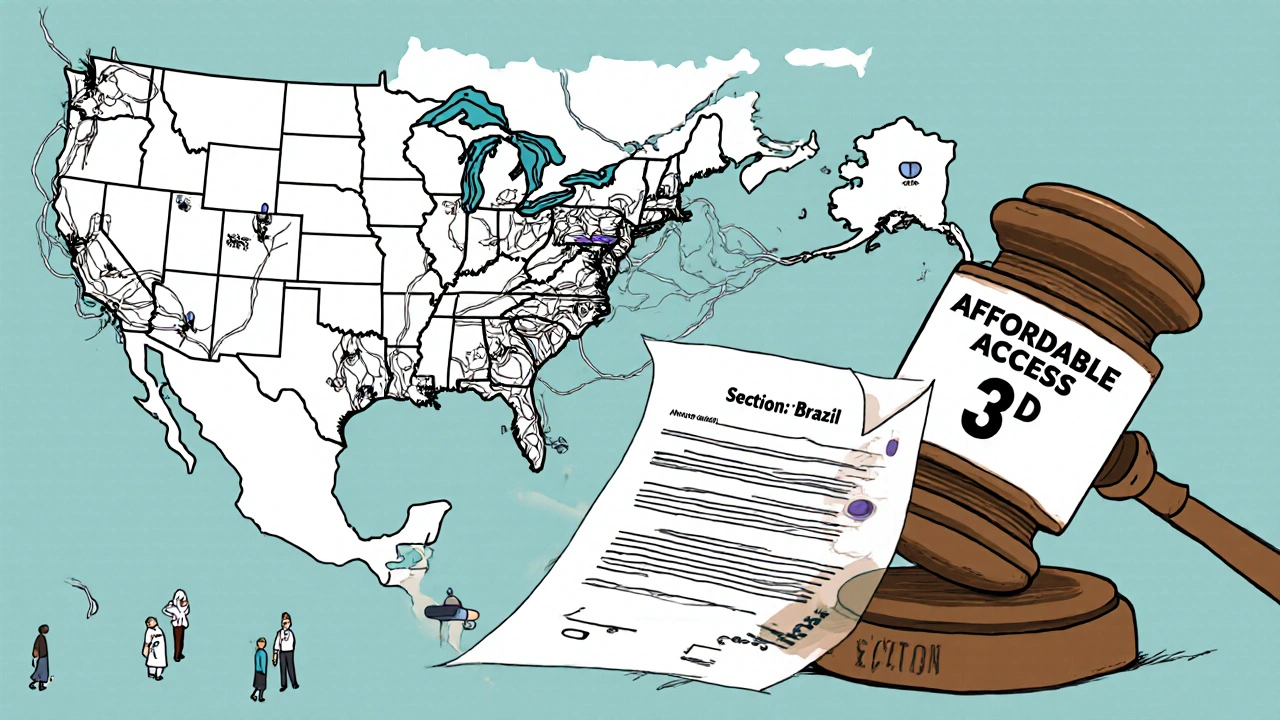

India took a different path. Its 2005 Patents Act includes Section 3(d), which says you can’t patent a new form of a known drug unless it shows significantly better efficacy. That’s why Novartis lost its fight to patent a modified version of Gleevec. The Indian Supreme Court ruled it wasn’t a real innovation-just a tweak.

Brazil requires approval from its health ministry before granting pharmaceutical patents. The European Union demands proof of "significant clinical benefit" for certain secondary patents. These aren’t just legal differences-they’re policy choices. They’re about balancing innovation with access.

As a result, drugs like Humira and Enbrel hit generic markets in India and Brazil years before they did in the U.S. Patients there get cheaper options sooner. In the U.S., they wait.

Who Benefits-and Who Pays

The pharmaceutical industry defends secondary patents as necessary for innovation. PhRMA argues they fund new treatments for rare diseases and improve safety. They point to studies showing secondary patents contribute $14.7 billion annually to R&D.But here’s the disconnect: the vast majority of these patents aren’t for breakthroughs. They’re for drugs that already make billions. Jena & Seabury’s 2012 study found that companies are 17% more likely to file a secondary patent for every extra billion dollars a drug earns. In other words, the more money a drug makes, the harder companies fight to keep it exclusive.

Meanwhile, generic manufacturers-who produce 90% of U.S. prescriptions-face a legal minefield. They have to check every patent, every claim, every possible loophole. One misstep, and they get sued. Many never even try.

And patients? They’re caught in the middle. They’re told the new version is better. But they’re paying more for something that often works the same way.

The Future: Tighter Rules, Tougher Challenges

Change is coming. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act in the U.S. lets Medicare challenge certain secondary patents. The European Commission’s 2023 Pharmaceutical Strategy explicitly targets "patent thickets." The World Health Organization now calls secondary patents the top legal barrier to medicine access in 68 low- and middle-income countries.Courts are also getting stricter. The 2023 Amgen v. Sanofi decision limited how broadly antibody patents can be claimed-a warning shot to companies trying to stretch patent coverage too far.

Experts predict that by 2027, companies will need to prove their secondary patents offer real clinical value-not just legal convenience. Otherwise, regulators and the public will push back harder.

For now, the system still favors the big players. Pfizer alone holds over 14,000 active secondary patents. But the tide is turning. More governments are asking: Is this innovation-or just exploitation?

When a drug’s original patent expires, the public expects competition. That’s how prices drop. That’s how access grows. Secondary patents don’t always deliver that. Sometimes, they just delay it.

Are secondary patents legal?

Yes, secondary patents are legal in most countries, including the U.S., Canada, and the EU. But their validity depends on whether they meet patentability standards-novelty, non-obviousness, and utility. Countries like India and Brazil have stricter rules and have blocked many secondary patents that don’t show real therapeutic improvement.

How long do secondary patents last?

Like primary patents, secondary patents last 20 years from the filing date. But because they’re often filed years after the original patent, they can extend market exclusivity by 4 to 11 years beyond the original term. For drugs without strong primary patents, secondary patents can add nearly a decade of protection.

Do secondary patents lead to better drugs?

Sometimes. A few secondary patents have led to real improvements-like reduced side effects, easier dosing, or new uses for old drugs. But studies show only about 12% of secondary patents correspond to clinically meaningful benefits. Most are minor changes designed to delay competition, not improve care.

Why do generic companies struggle to challenge secondary patents?

Because the patent landscape is complex and expensive. Generic manufacturers must file legal challenges (called Paragraph IV certifications) against each listed patent. If they lose, they face massive damages. Legal costs average $15-20 million per drug, and only 38% of challenges succeed. Many simply can’t afford to fight.

Can I tell if my medication is protected by a secondary patent?

Not easily. The FDA’s Orange Book lists only certain types-formulation and method-of-use patents. Others, like polymorph or manufacturing patents, are hidden. If your drug is still expensive years after its original patent expired, there’s a good chance secondary patents are still in play. Ask your pharmacist or check Drug Patent Watch’s public database.

What’s being done to stop abuse of secondary patents?

Several countries are tightening rules. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act lets Medicare challenge questionable patents. The EU now requires proof of clinical benefit. India and Brazil block patents on minor chemical changes. Legal scholars and public health groups are pushing for reforms that prioritize patient access over corporate profits.

What Comes Next?

The era of unchecked secondary patenting may be ending. As public pressure grows and courts demand more proof of innovation, companies will need to do more than just tweak a molecule. They’ll need to deliver real improvements-or face rejection.For now, the system still works in favor of big pharma. But the balance is shifting. The question isn’t whether secondary patents exist-it’s whether they’re serving patients, or just profits.

November 30, 2025 AT 01:52

India’s Section 3(d) is the only sane approach. If you’re just tweaking a molecule for patent extensions, you’re not innovating-you’re gaming the system. The Supreme Court got it right with Novartis. Patients shouldn’t pay extra for color changes.