Every time you take an antibiotic when you don’t need it, you’re not just helping yourself-you’re helping bacteria become stronger. That’s the harsh truth behind the growing crisis of antibiotic resistance. It’s not science fiction. It’s happening right now, in hospitals, farms, and even your own home. Bacteria aren’t magically immune-they evolve. And they’re evolving faster than we can keep up.

How Bacteria Outsmart Antibiotics

Antibiotics don’t kill bacteria because they’re strong. They kill because they target specific weaknesses-like the cell wall, protein production, or DNA replication. But bacteria don’t sit still. When exposed to antibiotics, even at low doses, they mutate. And some of those mutations give them a survival edge.There are five main ways bacteria fight back:

- Reduce entry: They change their outer membrane so the antibiotic can’t get inside.

- Pump it out: Special proteins act like tiny vacuums, ejecting the drug before it does damage.

- Change the target: If the antibiotic is meant to bind to a protein, the bacteria alter that protein so the drug no longer fits.

- Destroy the drug: Some bacteria produce enzymes that break down antibiotics-like penicillinase, which neutralizes penicillin.

- Find a new path: They bypass the biological process the antibiotic blocks by using a different metabolic route.

Research from 2024 shows that when bacteria like Yersinia enterocolitica and Escherichia coli are exposed to gradually increasing doses of antibiotics, they don’t just get resistant-they get hyper-resistant. In one study, minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) jumped sixfold. That means the same dose that once killed them now does nothing.

The Hidden Timeline of Resistance

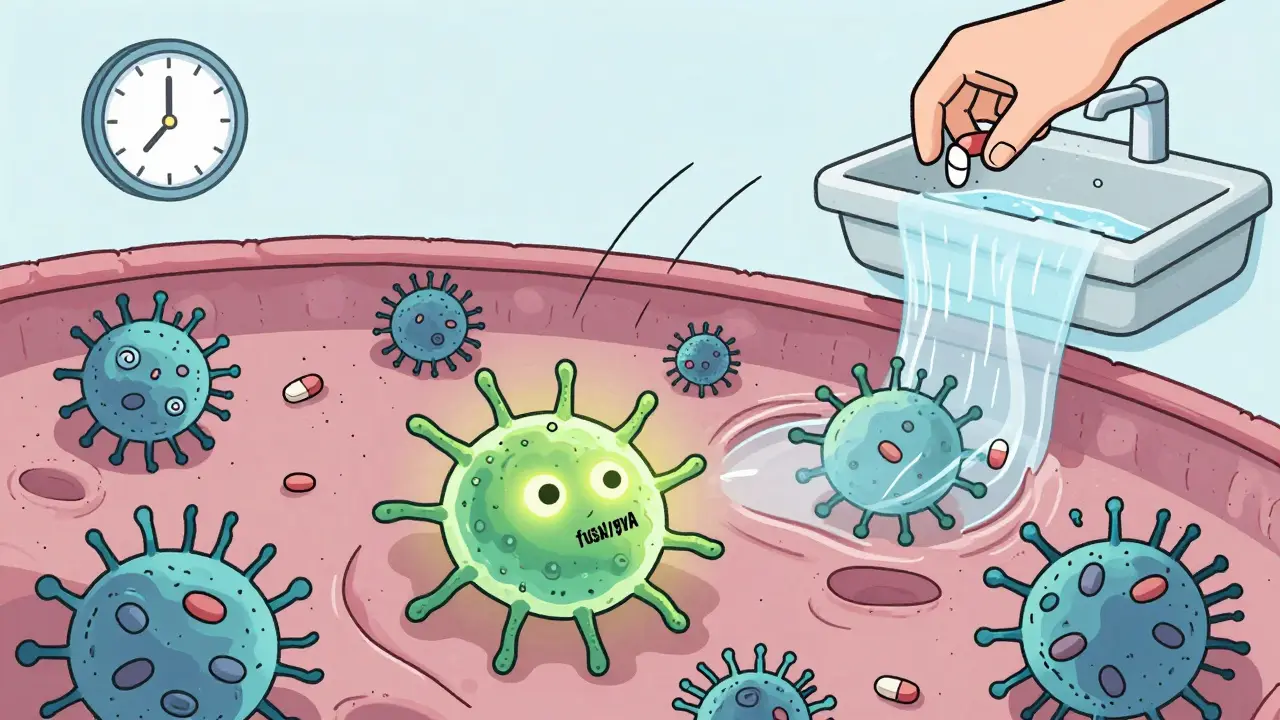

Resistance doesn’t happen overnight. It’s a race between mutation and selection. Early on, bacteria rely on quick, reversible changes-like adding chemical tags to their DNA (methylation). These tweaks can turn genes on or off without changing the actual code. It’s like flipping a switch: fast, temporary, and easy to reverse.But if the pressure stays, something more permanent kicks in. After about 150 generations in dynamic environments (like a body under treatment), mutations start locking in. Genes like fusA, gyrA, and parC begin to change permanently. These mutations are passed on to future generations. And once they’re fixed in the population, resistance becomes stable-even if you stop using the antibiotic.

Here’s the twist: most early mutations don’t stick around. Studies show only 8% to 20% of mutations seen in the first few weeks survive to the end. Bacteria are constantly testing new changes. The ones that work replace the old ones. It’s evolution in fast-forward.

When Antibiotics Aren’t the Culprit

You might think only antibiotics cause resistance. But that’s not true. New research shows that common non-antibiotic drugs-like antidepressants, antihistamines, and even some painkillers-can trigger bacteria to take up resistance genes from their environment. This process, called transformation, lets bacteria steal resistance from dead neighbors. It’s like picking up a spare key from the sidewalk and using it to break into your house.Even more alarming: tetracycline resistance doesn’t always come from mutating the drug’s target. Sometimes, it comes from breaking a genetic brake. In one study, a transposon-a kind of jumping gene-inserted itself into the promoter region of the acrAB operon. This turned on a powerful efflux pump that had nothing to do with tetracycline before. Suddenly, the bacteria could pump out the drug. The mutation wasn’t in the target. It was in the switch.

The Bigger Picture: One Health, One Problem

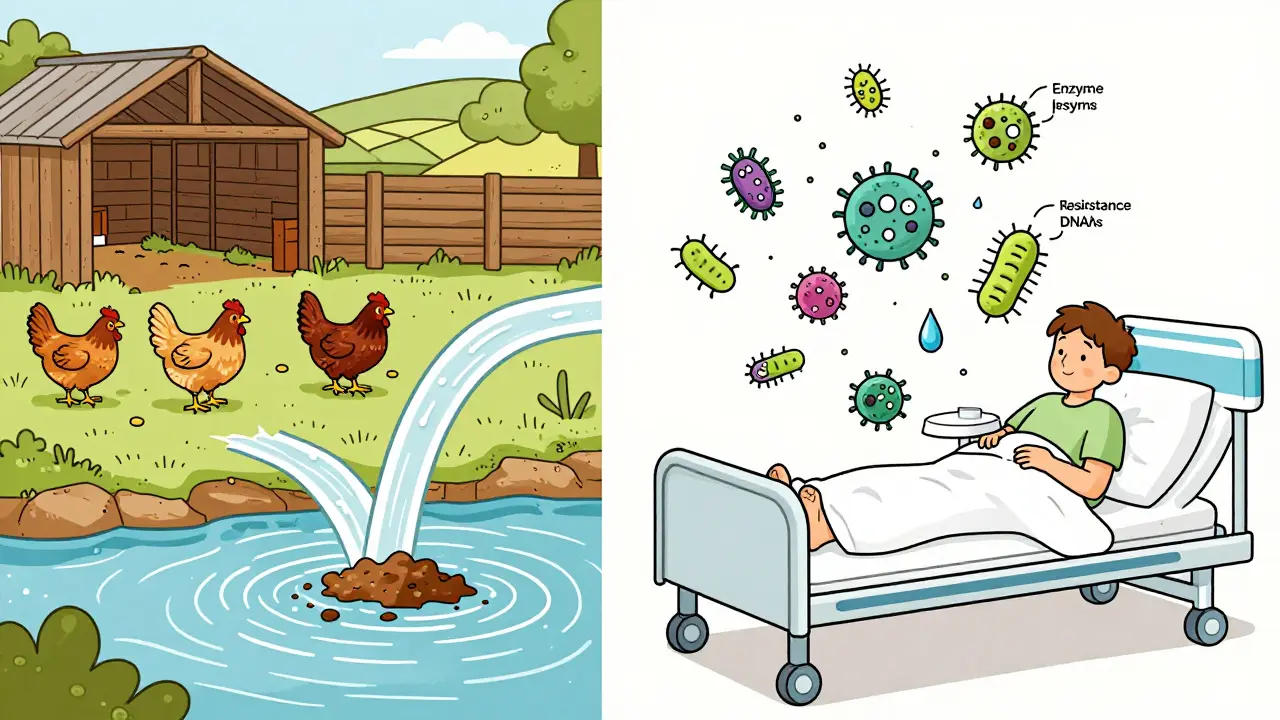

Antibiotic resistance isn’t just a human health issue. It’s a farm issue, a water issue, a wildlife issue. Antibiotics are used heavily in livestock-to treat sick animals, yes, but also to make them grow faster. These drugs end up in manure, which runs into rivers and soil. Resistant bacteria hitchhike on food, in dust, and in wastewater.The World Health Organization calls this the One Health approach: human, animal, and environmental health are linked. You can’t fix resistance in hospitals if it’s spreading from chicken farms or polluted rivers. That’s why countries like Australia, Sweden, and the Netherlands have banned antibiotic growth promoters in livestock. Their resistance rates have dropped as a result.

How We’re Misusing Antibiotics

In the U.S., about 30% of outpatient antibiotic prescriptions are unnecessary. That’s 47 million courses a year given for viral infections-colds, flu, sore throats caused by viruses. Antibiotics don’t work on viruses. But patients ask for them. Doctors sometimes give them to avoid conflict or because they’re rushed.In Australia, we’re better than the U.S. but still not good enough. A 2023 study found that nearly 1 in 5 antibiotic scripts in community pharmacies were for conditions that didn’t need them. The same goes for hospitals. A patient gets a fever after surgery. Instead of waiting for culture results, they get broad-spectrum antibiotics “just in case.” That’s not precaution. That’s overkill.

And it’s not just quantity-it’s timing. Taking antibiotics for too short a time leaves behind the toughest survivors. Taking them too long kills off good bacteria and gives resistant ones room to take over. The rule used to be “finish the whole course.” Now, experts say: take only as long as needed. For many infections, 5 days is enough. For others, 3.

What’s Being Done-And What’s Not

There are 67 new antibiotics in development worldwide. Only 17 target the bacteria the WHO says are most dangerous. Just three are truly new-designed to bypass existing resistance mechanisms. The rest are tweaks on old drugs. That’s not innovation. That’s tinkering.Meanwhile, diagnostics lag behind. Doctors still guess what’s causing an infection. Culture tests take days. Rapid tests? They exist-but aren’t widely used. In Australia, only 20% of hospitals have access to real-time molecular diagnostics that can detect resistance genes within hours.

But there’s hope. CRISPR-based tools are being tested to cut resistance genes out of bacterial DNA. Metabolomics is revealing how bacteria rewire their energy use to survive antibiotics. And AI models are now predicting which mutations will emerge next, based on genetic patterns across thousands of strains.

Antibiotic stewardship programs-where hospitals track prescribing and educate staff-have cut unnecessary use by 20-30% in places that stick with them. But they take 12 to 18 months to show results. Most clinics don’t have the patience-or funding-to wait.

What You Can Do

You don’t need to be a doctor to fight resistance. Here’s what actually works:- Don’t ask for antibiotics. If your doctor says it’s a virus, believe them. Ask about symptom relief instead.

- Take them exactly as prescribed. No skipping doses. No stopping early. No saving leftovers for next time.

- Never share antibiotics. A dose that worked for your friend might be the wrong one for you-or even dangerous.

- Wash your hands. Simple, but it stops the spread of resistant bugs before they even get a chance.

- Choose meat raised without routine antibiotics. Look for labels like “no antibiotics ever” or “organic.”

These aren’t just good habits. They’re survival tactics. The next superbug could be resistant to every drug we have. And if we keep using antibiotics like candy, it’s only a matter of time.

The Cost of Inaction

Right now, antibiotic resistance kills 1.27 million people a year globally. In Europe, it’s 33,000. In Australia, it’s over 1,000. By 2050, if nothing changes, that number could jump to 10 million a year-more than cancer.The economic toll? Over $1 trillion lost annually. 24 million people pushed into extreme poverty. Hospitals will stop doing surgeries. C-sections, hip replacements, chemotherapy-all become death sentences if infections can’t be controlled.

We’re not running out of antibiotics because science failed. We’re running out because we used them carelessly. The tools to fix this exist. What’s missing is urgency.

Can you get antibiotic resistance from taking them too often?

Yes. Every time you take an antibiotic, you kill off the susceptible bacteria-but leave behind the ones with resistance mutations. Over time, those resistant strains multiply and spread. It’s not your body that becomes resistant-it’s the bacteria living in and on you.

Are natural remedies like honey or garlic effective against resistant infections?

Some natural substances, like medical-grade honey, have shown antibacterial properties in wounds and may help with minor infections. But they are not substitutes for antibiotics in serious infections like pneumonia, sepsis, or meningitis. Relying on them instead of proven treatments can be deadly.

Why don’t we have more new antibiotics?

Developing a new antibiotic costs over $1 billion and takes 10-15 years. Most pharmaceutical companies don’t see a return on investment because antibiotics are used for short courses, not lifelong like cholesterol drugs. There’s little profit in curing people quickly.

Can you become immune to antibiotics?

No. Your body doesn’t build immunity to antibiotics. What changes is the bacteria. They evolve to survive the drug. You can still get infected by resistant strains even if you’ve never taken antibiotics yourself.

Is antibiotic resistance only a problem in hospitals?

No. Hospitals are hotspots, but resistance is everywhere. It’s in the soil, rivers, food supply, pets, and even your kitchen sink. Community-acquired resistant infections are rising fast, especially in urinary and skin infections.

What Comes Next?

The future isn’t about finding one magic bullet. It’s about changing how we think about bacteria. We need faster diagnostics, smarter prescribing, global cooperation, and better waste management. We need farmers to stop routine antibiotic use. We need governments to fund real innovation-not just tweaks.And we need to stop treating antibiotics like they’re infinite. They’re not. They’re a finite resource-like clean water or breathable air. Once they’re gone, we won’t get them back.

The bacteria won’t wait. Neither should we.

December 26, 2025 AT 20:27

antibiotics arent magic pills theyre tools and we keep treating them like candy. i used to take them for every cold till my body started feeling like a warzone. now i just drink tea and wait it out. bacteria dont care if you feel bad they just wanna survive.