As of December 2025, more than 270 medications are still in short supply across the United States - a number that may seem lower than last year’s peak, but still represents a persistent crisis in healthcare. For patients, this isn’t just a logistical headache. It’s a real threat to treatment, recovery, and sometimes life itself. If you or someone you know relies on chemotherapy, IV fluids, or even common antibiotics, you’re likely feeling the pinch. These aren’t rare edge cases. These are everyday drugs that hospitals and clinics can’t reliably get their hands on.

What’s Actually in Short Supply Right Now?

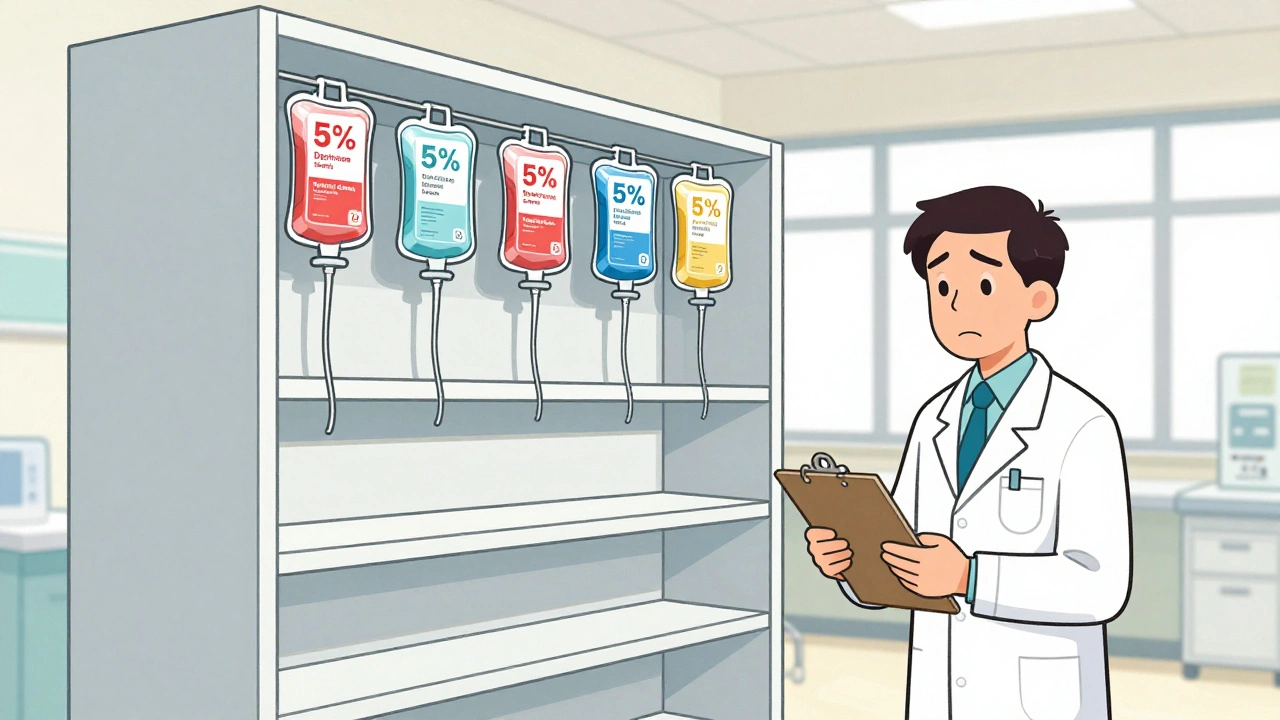

The most critical shortages are in sterile injectable medications, especially those used in hospitals. These aren’t pills you can pick up at the pharmacy. They’re life-sustaining treatments given intravenously - and when they’re gone, there’s often no easy substitute.- 5% Dextrose Injection (small volume bags): In shortage since February 2022. Expected to resolve in August 2025. Used for hydration, delivering medications, and treating low blood sugar.

- 50% Dextrose Injection: Shortage since December 2021. Resolution expected September 2025. Critical for emergency hypoglycemia treatment.

- Cisplatin: A cornerstone chemotherapy drug for testicular, ovarian, and lung cancers. Production halted after a 2022 FDA inspection found quality violations at an Indian manufacturing plant. Hospitals are rationing doses, prioritizing patients with the highest survival benefit.

- Vancomycin and Meropenem: Antibiotics used for severe infections. Shortages have forced doctors to use older, less effective, or more toxic alternatives.

- Normal Saline (0.9% Sodium Chloride): The most common IV fluid in the world. Still in limited supply despite efforts to ramp up production. Used in nearly every emergency room, ICU, and operating room.

- Levothyroxine: The standard treatment for hypothyroidism. Demand has surged, and supply chains haven’t kept up. Patients report inconsistent dosing and unavailability at multiple pharmacies.

- GLP-1 agonists (e.g., semaglutide, tirzepatide): While often associated with weight loss, these drugs are also used for type 2 diabetes. Demand has climbed 35% annually since 2020. Manufacturers can’t keep up, leading to rationing and delays for diabetic patients.

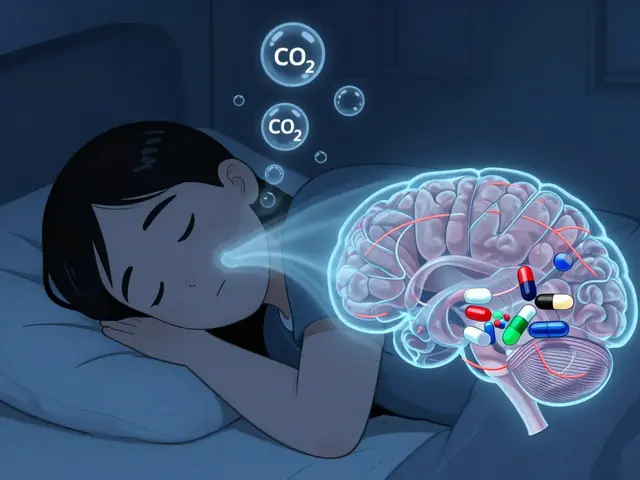

- Midazolam and Fentanyl: Used for sedation and pain control during procedures. Shortages have forced delays in surgeries and emergency interventions.

These aren’t random picks. They’re the drugs listed in the ASHP Drug Shortages Database as active in April 2025 - and many have been on the list for over two years. Some have been resolved. Others are stuck in limbo because the factories making them are still under FDA scrutiny or can’t get raw materials.

Why Are These Drugs So Hard to Find?

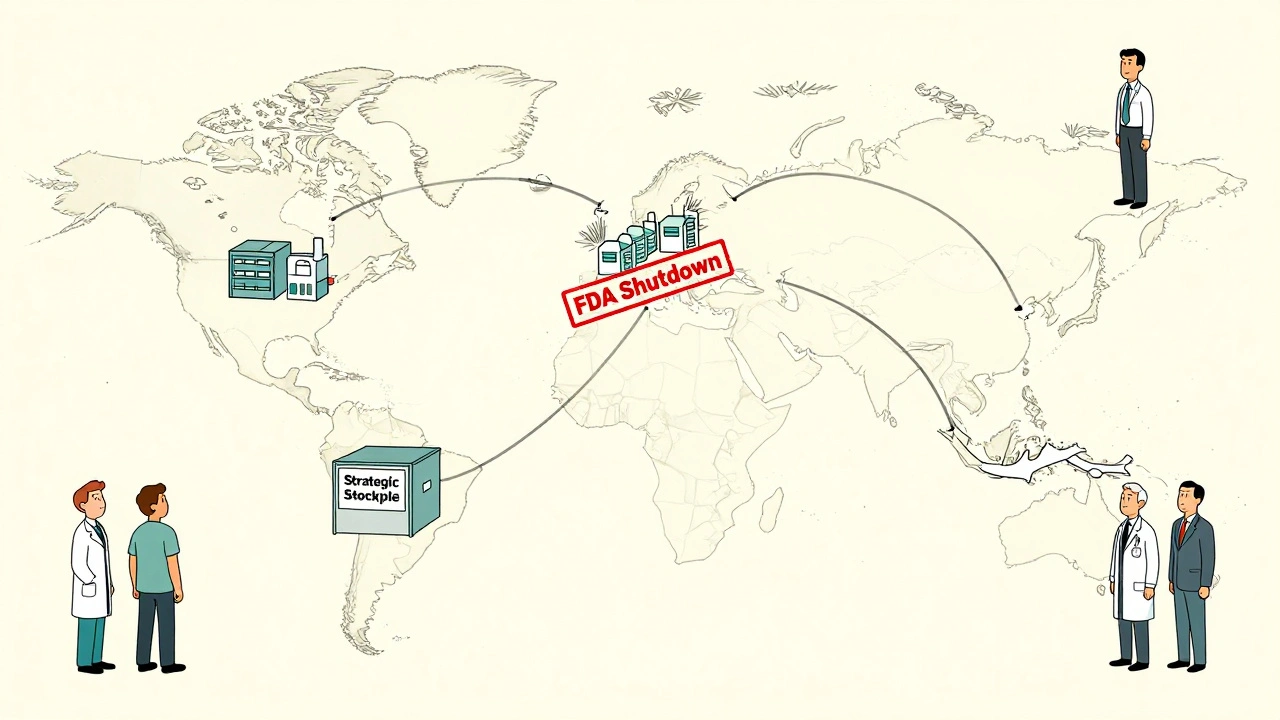

It’s not one problem. It’s a chain of failures.First, most of the active ingredients - the actual medicine - come from overseas. About 60% of the U.S. supply of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) comes from just three countries: India, China, and the European Union. India alone supplies nearly half of all APIs. But these countries don’t just make the medicine. They also make the containers, the filters, the tubing - everything needed to turn powder into a sterile IV bag.

When a single plant in India fails an FDA inspection - like the one that made cisplatin - it can knock out 50% of the U.S. supply overnight. No backup. No redundancy. Just silence.

Then there’s the money problem. Generic drugs make up 90% of prescriptions but only 20% of pharmaceutical revenue. Manufacturers squeeze margins to 5-8% on these drugs. Meanwhile, brand-name drugs like GLP-1 agonists have margins of 30-40%. So when a company has to choose between investing in a low-profit generic or a high-profit brand, the generic loses. Even if it’s the drug that saves lives.

And when demand spikes - like with semaglutide for weight loss - there’s no surge capacity. Factories are running at full tilt. No extra machines. No spare workers. Just a system built for efficiency, not resilience.

Who’s Getting Hurt?

It’s not just patients. It’s everyone in the system.Hospital pharmacists spend over 10 hours a week just tracking down drugs. In one Ohio hospital, a pharmacist told Reddit users they had to assign cisplatin doses based on cancer type - testicular cancer patients got priority because survival rates drop sharply without it. Other patients waited weeks.

Doctors are forced to substitute. Sometimes it works. Sometimes it doesn’t. A 2024 AMA survey found 43% of physicians had to switch to less effective drugs. That means longer hospital stays. More side effects. Lower survival rates.

Patients with cancer are hit hardest. One advocacy group found that 31% of cancer patients experienced treatment delays in 2024 - an average of nearly two weeks per delay. For someone with aggressive cancer, those two weeks can mean the difference between remission and progression.

Even routine care suffers. A diabetic patient who can’t get levothyroxine for more than a few days risks heart problems, depression, and fatigue. A child with an infection who can’t get vancomycin might need a more toxic alternative that damages kidneys.

What’s Being Done?

There’s no magic fix - but there are small steps.The FDA has started a new public portal where doctors and pharmacists can report shortages before they’re officially listed. In its first three months, it received over 1,200 reports - and acted on 87% of them. That’s progress.

Some states are taking action. New York is building an online map showing which pharmacies still have scarce drugs. Hawaii now allows Medicaid to cover drugs approved in other countries if they’re not available here - a controversial move, but one that’s keeping people alive.

Pharmacists in 47 states can now substitute similar drugs without a new prescription. But only 19 states let them do it without even calling the doctor. That’s a huge barrier when time is critical.

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists has published guidelines for conserving IV fluids: use oral rehydration when possible, reduce unnecessary IVs, and optimize doses. Hospitals are trying. But it’s not enough.

What’s Next?

Without major policy changes, the situation won’t improve. The Congressional Budget Office predicts shortages will stay above 250 through 2027. If proposed tariffs on Chinese and Indian pharmaceuticals go through - as some lawmakers are pushing - shortages could jump to 350 or more.Experts agree on three fixes:

- Incentivize domestic manufacturing: Tax breaks, grants, or guaranteed contracts to bring API production back to the U.S. or allied countries.

- Build strategic stockpiles: The government should hold reserve supplies of the 50 most critical drugs - not just for emergencies, but for routine shortages.

- Create a real-time early warning system: Link data from manufacturers, distributors, and hospitals so shortages are predicted, not just reported after they happen.

Right now, we’re reacting. We need to be preparing.

What Should You Do?

If you’re a patient:- Call your pharmacy ahead of time to check if your medication is available.

- Ask your doctor if there’s a therapeutically equivalent alternative.

- Don’t stop your medication without talking to your provider - even if it’s hard to find.

- Join patient advocacy groups. Your voice matters.

If you’re a caregiver or family member:

- Keep a list of all medications your loved one takes - including dosages and reasons.

- Know the generic names. Brand names change. Generics don’t.

- Be persistent. If one pharmacy doesn’t have it, call five more.

This isn’t about blaming manufacturers or regulators. It’s about recognizing that a system built for profit over preparedness is failing real people. The drugs are still out there - just not where they need to be, when they need to be there. Until we fix the supply chain, we’ll keep living with this crisis - one missed dose at a time.

What are the most common drugs in short supply right now?

As of late 2025, the most common shortages include sterile injectables like 5% and 50% Dextrose, normal saline, cisplatin, vancomycin, midazolam, fentanyl, levothyroxine, and GLP-1 agonists like semaglutide. These are used for cancer treatment, infection control, emergency care, and chronic disease management. Many have been in shortage for over two years.

Why are generic drugs more likely to be in short supply than brand-name drugs?

Generic drugs make up 90% of prescriptions but only generate about 20% of pharmaceutical revenue. Manufacturers make only 5-8% profit margins on them, compared to 30-40% for brand-name drugs. With thin profits, companies have little incentive to invest in backup production lines, quality upgrades, or domestic manufacturing. When a factory shuts down, there’s often no one else ready to step in.

Can I switch to a different medication if mine is unavailable?

Sometimes, yes - but only under medical supervision. Many drugs have therapeutically equivalent alternatives. For example, if cisplatin is unavailable, carboplatin may be used instead for some cancers. But these substitutes aren’t always as effective or safe. Never switch on your own. Talk to your doctor or pharmacist about what’s available and what’s safe for your condition.

How are hospitals managing these shortages?

Hospitals are using several strategies: rationing critical drugs (like giving cisplatin only to patients with the highest survival benefit), conserving IV fluids by switching to oral hydration when possible, substituting with similar medications, and increasing inventory audits. Many pharmacists now spend over 10 hours a week just tracking down drugs. Some hospitals have started building 30-day stockpiles, but only 28% can afford to do so.

Is there a way to know if my pharmacy has the drug I need?

Yes - but it’s not perfect. The ASHP Drug Shortages Database lists which drugs are scarce and which manufacturers are affected. Some states, like New York, are launching online maps showing which local pharmacies have stock. Call ahead. Ask for the generic name. Check multiple locations. Don’t assume your usual pharmacy will have it.

Will new laws fix drug shortages?

Current laws like the Drug Shortage Prevention Act require manufacturers to report disruptions, but they don’t force them to fix them. Proposed bills aim to create financial incentives for domestic production, mandate strategic stockpiles, and build a national early warning system. Without these changes, shortages will remain common. The FDA can prevent about 200 potential shortages a year - but only if manufacturers tell them early. Too often, they don’t.

Final Thoughts

Drug shortages aren’t going away quietly. They’re a symptom of a system that prioritizes cost over resilience. We’ve outsourced production. We’ve underfunded backups. We’ve waited for crises to happen before we act. The result? Patients are left waiting - sometimes too long.The solutions exist. They’re not expensive. They’re not theoretical. They’re just political. Until we treat drug supply as a public health priority - not a market afterthought - this crisis will keep coming back. And the next person who misses a dose? It might be someone you love.

December 11, 2025 AT 01:41

why is everythng always broken?? like wtf is wrong with us?? we cant even make saline anymore??