POI Risk Calculator

This calculator estimates your risk of postoperative ileus (POI) based on your surgery type, opioid use, and recovery plan. POI can delay your recovery and increase hospital stays.

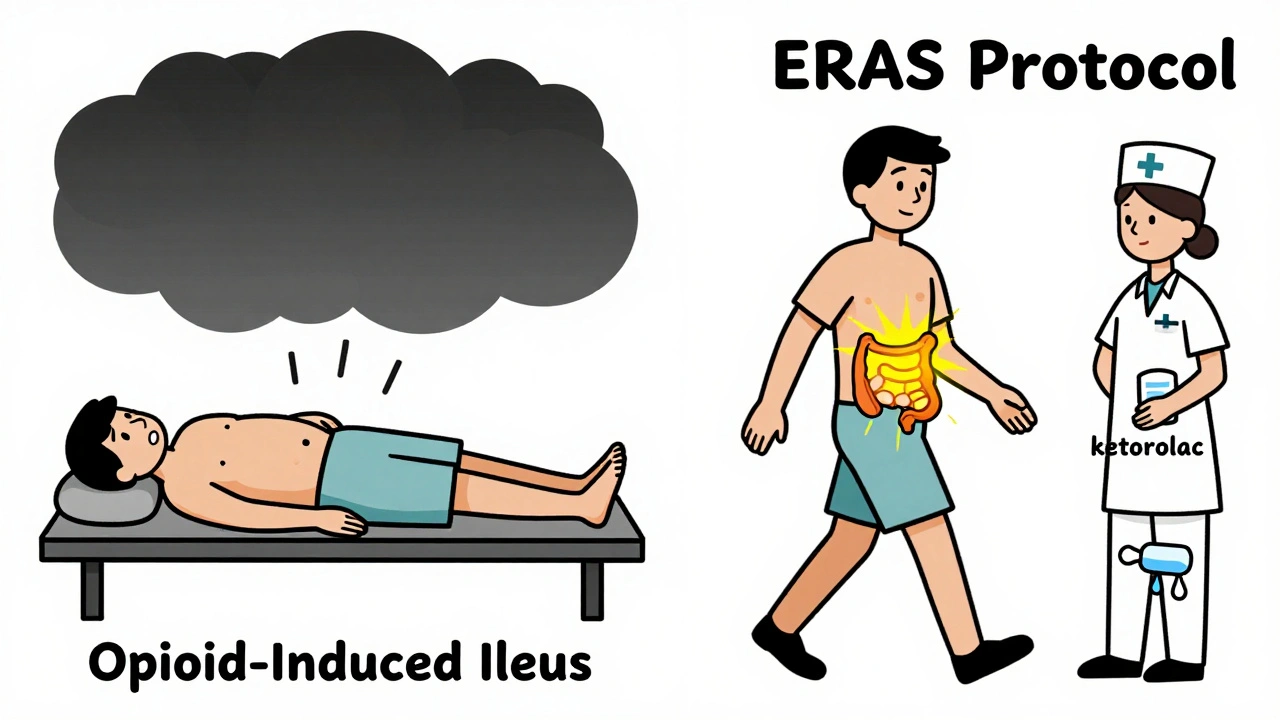

After surgery, many patients expect to feel better-but instead, they’re stuck with bloating, nausea, and no bowel movement for days. This isn’t just discomfort. It’s postoperative ileus (POI), a common and costly complication fueled heavily by the very drugs meant to control pain: opioids. While surgery itself triggers gut slowdown, opioids make it worse-often doubling recovery time. The good news? We now know exactly how to stop it.

What Exactly Is Postoperative Ileus?

Postoperative ileus isn’t a blockage. It’s a temporary paralysis of the intestines. After surgery, your gut stops moving food and gas the way it should. You might feel full, bloated, nauseous, and unable to eat. You won’t pass gas or have a bowel movement for days. This isn’t normal. When it lasts more than three days, it’s clinically significant-and it’s often opioid-driven.Up to 70% of patients undergoing major abdominal surgery develop POI. Even in orthopedic procedures like hip replacements, rates hit 20-25% when opioids are used heavily. The result? Longer hospital stays, higher costs, and more readmissions. In the U.S., POI adds 2-3 days to hospital stays and costs the system $1.6 billion every year.

Why Opioids Are the Main Culprit

Opioids work by binding to receptors in the brain to dull pain. But they also bind to receptors in your gut-specifically, mu-opioid receptors in the myenteric plexus, the nerve network that controls intestinal movement. When activated, these receptors slow down or shut off contractions in your stomach and intestines.Studies show that just 5-10 mg of morphine per hour can delay gastric emptying by 50-200%. In animal models, opioid exposure reduces colonic motility by up to 70%. The effects start within 24-72 hours after surgery and can last for days. Patients on high-dose opioids report hard stools (46-81% of cases), straining (59-77%), bloating (40-61%), and delayed bowel movements.

It’s not just the drugs you’re given. Your body also releases its own opioids during surgical stress. This natural surge compounds the problem. Combine that with inflammation from the surgery and increased sympathetic nervous system activity-and you’ve got the perfect storm for gut shutdown.

Traditional Treatments Don’t Work Well

For years, the go-to fix was a nasogastric tube to drain stomach contents. But studies show it only reduces POI duration by 12%-barely better than doing nothing. IV fluids, bed rest, and waiting it out? They’re still common, but they don’t address the root cause.One outdated belief is that bowel sounds need to return before you can eat. That’s false. You don’t need to hear gurgling to start sipping water. Delaying oral intake only makes POI worse by starving the gut of stimulation.

Another myth: you need to wait for a bowel movement before going home. That’s not necessary. If you can tolerate 1,000 mL of fluids and pass gas, you’re likely ready for discharge-even if you haven’t pooped yet.

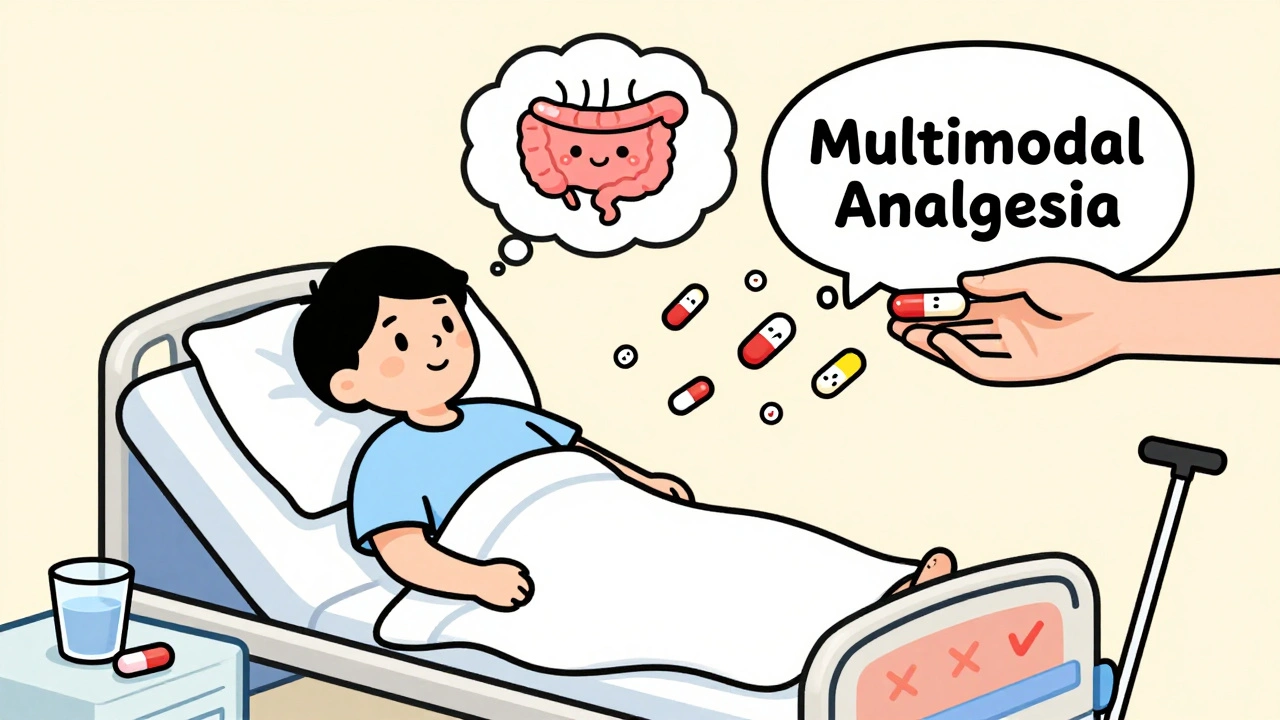

The Real Solution: Multimodal Analgesia

The best way to prevent POI isn’t to treat it-it’s to avoid triggering it in the first place. That means cutting back on opioids. Not eliminating them, but reducing them smartly.Research from the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society shows that limiting opioids to under 30 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) in the first 24 hours cuts POI rates from 30% to just 18%. How? By using non-opioid painkillers upfront.

- Acetaminophen (IV): 1 gram every 6 hours. Reduces opioid needs by 20-30%.

- Ketorolac (IV): 30 mg every 6-8 hours (if kidney function is normal). A strong NSAID that works as well as opioids for many types of pain.

- Regional anesthesia: Epidurals or nerve blocks cut opioid use by up to 50% and reduce POI duration from 5.2 days to 3.8 days.

One study found that patients who got this combo before and after surgery had 25% fewer cases of POI. And they left the hospital faster.

Peripheral Opioid Antagonists: The Targeted Fix

When opioids are necessary, there’s a drug that blocks their gut effects without touching pain relief: peripheral opioid receptor antagonists.Alvimopan (taken orally) and methylnaltrexone (given as a shot) work only in the intestines. They don’t cross the blood-brain barrier, so they don’t interfere with pain control.

Studies show alvimopan cuts time to bowel recovery by 18-24 hours in abdominal surgery patients. Methylnaltrexone speeds up bowel function by 30-40% in opioid-tolerant patients. These aren’t minor improvements-they’re game-changers.

But they’re not for everyone. They’re contraindicated if you have a true bowel obstruction (which happens in less than 0.5% of cases). And they’re expensive: methylnaltrexone costs $147.50 per 12mg dose. But for high-risk patients-those having abdominal surgery, or those who’ve never taken opioids before-the benefit far outweighs the cost.

Simple, Low-Tech Tricks That Work

You don’t always need drugs to fix this. Some of the most effective tools are free and simple:- Chew gum: Chewing three to four times a day after surgery tricks your brain into thinking you’re eating. This triggers gut motility. One nursing unit cut POI duration from 4.1 to 2.7 days by giving patients gum every 4 hours.

- Get up early: Walking within 4 hours of surgery reduces POI duration by 22 hours on average. Even just sitting in a chair helps. Movement stimulates the vagus nerve, which wakes up your gut.

- Drink early: Start sipping water or clear fluids within 6 hours after surgery. Don’t wait for bowel sounds.

These aren’t “nice-to-haves.” They’re essential parts of a proven protocol. In hospitals with strong ERAS programs, 85-90% of patients follow these steps-and their recovery times drop dramatically.

What Hospitals Are Doing Right (and Wrong)

Big academic hospitals have been leading the charge. Ninety-two percent use full ERAS protocols. They track daily: time to first flatus, time to first bowel movement, and ability to drink 1,000 mL without vomiting. If opioid use hits 40 MME in 24 hours, they automatically add a peripheral antagonist.But outside these centers? It’s still the Wild West. Community hospitals use only some elements. Rural hospitals? Only 28% have any formal POI prevention plan. The result? Patients in rural hospitals stay an extra 1.9 days on average.

Barriers? Resistance from anesthesiologists used to opioids. Nurses not trained to push early mobility. Poor documentation of opioid doses. One study found only 42% of nurses consistently helped patients get up within 6 hours.

But when hospitals fix these gaps, savings are huge. The University of Michigan cut average hospital stays by 1.8 days and saved $2,300 per patient. CMS now penalizes hospitals with high POI-related readmissions-$187,000 per facility on average. That’s money hospitals can’t afford to lose.

What’s Coming Next

The future of POI prevention is getting smarter:- AI prediction tools: Mayo Clinic’s model uses 27 pre-op factors-age, BMI, surgery type, meds-to predict POI risk with 86% accuracy. High-risk patients get preemptive treatment.

- Reformulated alvimopan: The original version was pulled in 2009 over heart concerns. A new extended-release version is in Phase III trials and could be available by 2026.

- Fecal transplants: Early pilot studies show microbiome restoration improves gut motility in stubborn POI cases.

- Naltrexone implants: Slow-release versions that block gut receptors for days are being tested in animals.

By 2027, experts predict comprehensive POI management will be standard care. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality estimates that if 90% of U.S. hospitals adopt these protocols, we could save $7.2 billion a year.

What You Can Do-Before and After Surgery

If you’re facing surgery:- Ask your surgeon: “What’s your plan to minimize opioids and prevent ileus?”

- Request regional anesthesia if possible.

- Ask about acetaminophen and ketorolac before and after surgery.

- Plan to chew gum and get out of bed within 4-6 hours after surgery.

- Don’t wait for bowel sounds to drink or eat.

If you’re a caregiver: Push for mobility. Bring gum. Remind nurses to track flatus and bowel movements. Don’t accept “it’s just normal after surgery” as an answer.

POI isn’t inevitable. It’s preventable. And the tools to stop it are already here.

How long does postoperative ileus usually last?

Without intervention, postoperative ileus typically lasts 3 to 5 days. With opioid-heavy pain management, it can stretch to 5-7 days or longer. When prevention strategies like multimodal analgesia and early mobility are used, recovery time drops to 1.5 to 3 days. The goal is to pass gas within 72 hours and have a bowel movement within 96 hours.

Can you get postoperative ileus without opioids?

Yes. Surgery itself triggers inflammation and nerve changes that slow the gut. But opioids make it significantly worse. Patients who avoid opioids entirely-like those using only regional anesthesia and NSAIDs-have POI rates as low as 8-12%. With high-dose opioids, rates jump to 30% or higher. Opioids aren’t the only cause, but they’re the most controllable one.

Is chewing gum really effective for preventing ileus?

Yes. Multiple studies confirm that chewing gum after surgery stimulates the cephalic-vagal reflex, signaling the gut to start moving again. One large trial showed patients who chewed gum four times daily passed gas 12 hours earlier and had bowel movements 16 hours sooner than those who didn’t. It’s simple, cheap, and has no side effects. Many hospitals now include it in their standard recovery protocols.

What’s the difference between alvimopan and methylnaltrexone?

Both block opioid receptors in the gut, but they’re used differently. Alvimopan is taken orally, usually twice a day for up to 7 days, and is approved for short-term use after bowel surgery. Methylnaltrexone is injected under the skin and is used for patients who are opioid-tolerant or need faster relief. Alvimopan is slightly more effective in abdominal surgery, while methylnaltrexone works better in patients already on long-term opioids. Neither works if there’s a physical blockage.

Can opioid withdrawal cause symptoms after surgery?

Yes. If a patient was on chronic opioids before surgery and then gets switched to oral pain meds too quickly, they can go into withdrawal. Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, anxiety, sweating, and diarrhea-often mistaken for worsening ileus. This happens in about 12% of cases. The fix is slow tapering, not abrupt stops. Always check pre-op opioid use before changing pain regimens.

How do I know if my hospital has a good POI prevention program?

Ask if they follow ERAS guidelines. Look for these signs: patients are encouraged to walk within 4 hours of surgery, they’re offered acetaminophen and NSAIDs before opioids, gum is provided, and staff track time to flatus and bowel movement. If they don’t track opioid doses in morphine milligram equivalents, or if they wait for bowel sounds before letting you eat, their protocol is outdated.

December 5, 2025 AT 17:11

This is actually one of the most thoughtful posts I’ve read on medical recovery. I’ve seen my uncle go through this after bowel surgery, and the gum trick was the only thing that seemed to help him feel human again. No joke-he was chewing like a cow by day two, and honestly? It worked.

Thanks for laying it out so clearly. Most docs just say ‘wait it out’ and call it a day.