Ear Drop Treatment: What Works, What Doesn't, and When to See a Doctor

When your ear hurts, it’s easy to grab any ear drop treatment, a liquid medication applied directly into the ear canal to treat infection, inflammation, or excess wax. Also known as otic drops, they’re one of the most common remedies people reach for—but using the wrong kind can make things worse. Not every ear pain is the same. Some infections live in the outer ear canal (otitis externa), while others hide behind the eardrum (otitis media). The drops that fix one won’t touch the other.

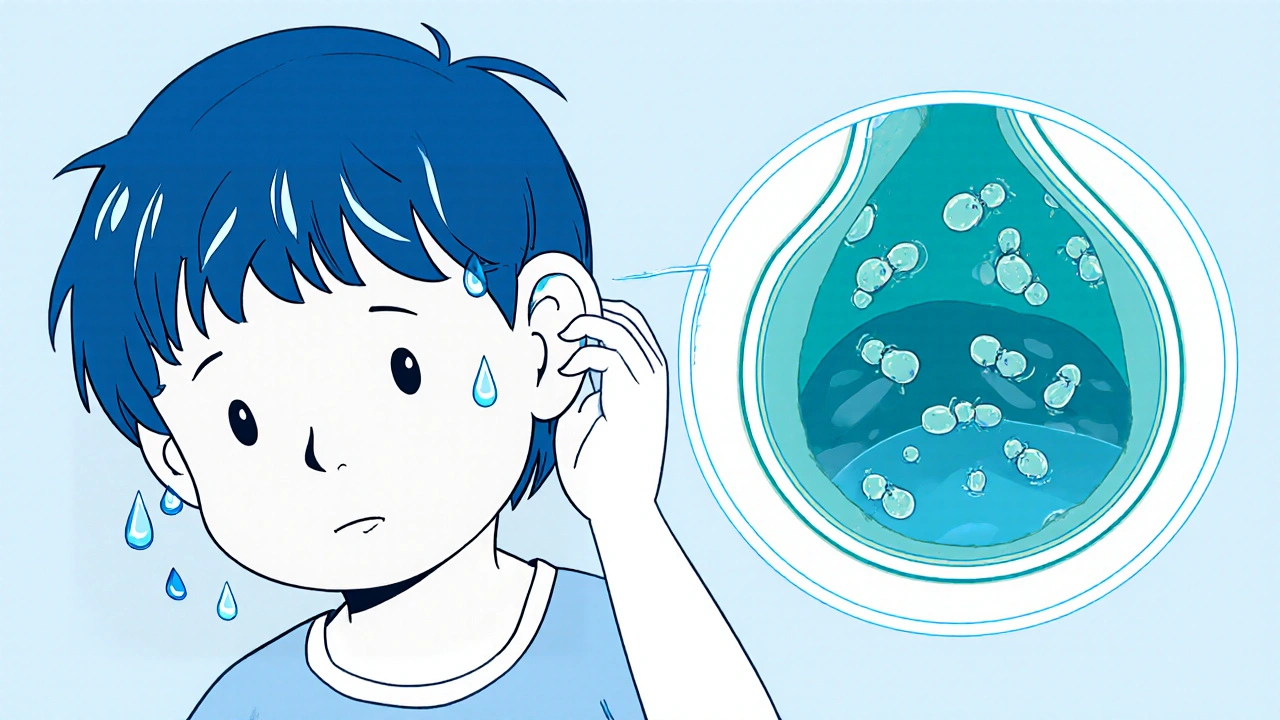

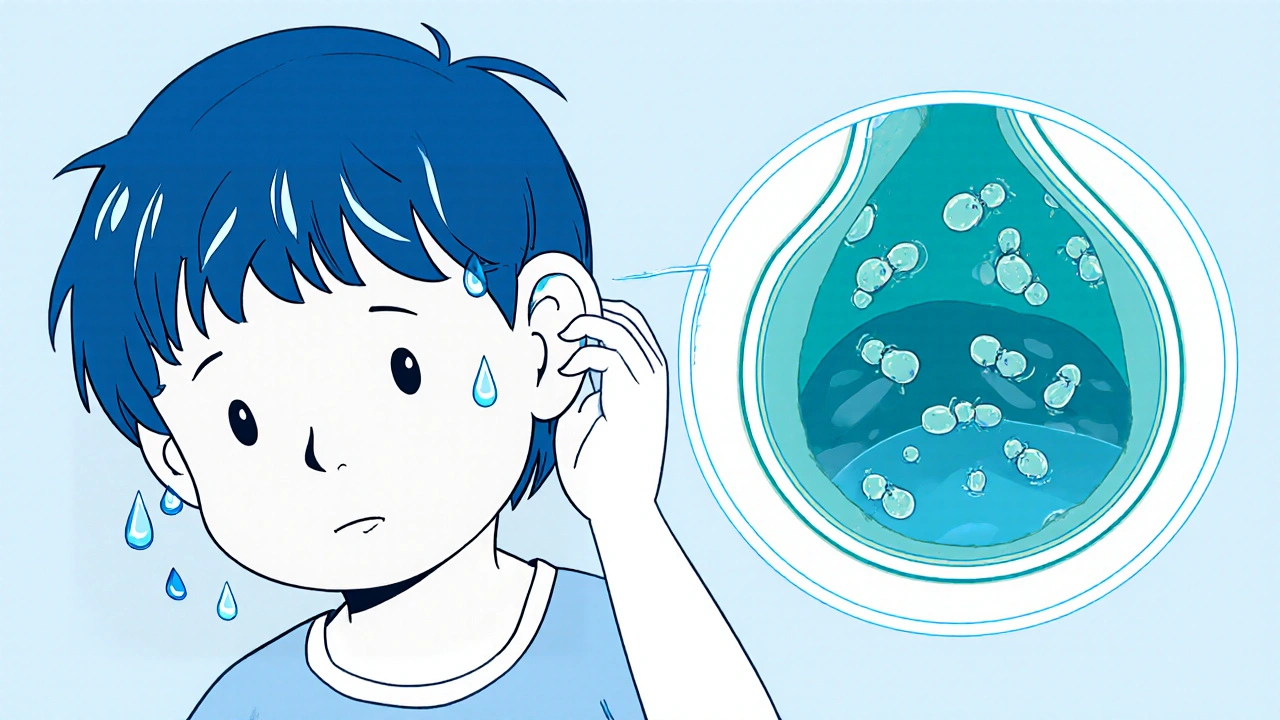

Most otitis externa, an infection of the ear canal often called swimmer’s ear responds well to antibiotic or steroid ear drops. These usually contain ingredients like ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, or hydrocortisone. They work right where the problem is—on the skin of the canal. But if your eardrum is ruptured or you have otitis media, a middle ear infection often caused by viruses or bacteria behind the eardrum, those same drops won’t help. In fact, putting drops in when the eardrum is damaged can cause more harm than good. That’s why doctors check your ear with an otoscope first.

Some people try home remedies like olive oil, vinegar, or garlic drops. These might feel soothing, but there’s little proof they kill infections. Worse, if you have a hidden perforation, even clean oil can lead to serious complications. And don’t assume that because a drop is sold over the counter, it’s safe for your situation. Many OTC ear drops are just for wax removal or temporary relief—they don’t treat infection.

Even when drops are right, how you use them matters. Lie on your side, pull the earlobe up and back (or down for kids), and let the drops sink in. Stay still for a minute so they reach deep. Don’t stick cotton swabs or anything else in after. And never use drops past their expiration date—bacteria can grow in them.

There’s also the issue of resistance. Overusing antibiotic ear drops, especially without a confirmed bacterial cause, can lead to strains that don’t respond to treatment. That’s why many cases of mild ear pain get better with just time, warmth, and pain relievers like ibuprofen. Antibiotics aren’t always needed—even when it feels like they are.

And then there’s the silent problem: hearing loss or dizziness that looks like an ear infection but isn’t. If your ear drops don’t help after a few days, or if you notice ringing, pressure, or balance issues, you’re not just dealing with a simple infection. Something else could be going on—like a fungal infection, a foreign object, or even a tumor. These aren’t common, but they’re real, and they need proper diagnosis.

What you’ll find below are real patient guides that cut through the noise. We’ve pulled together posts that break down exactly which ear drops work for which conditions, why some are prescribed over others, what side effects to watch for, and when skipping drops entirely is the smartest move. No guesswork. No marketing fluff. Just what the science says—and what actually helps people get better.

Swimmer’s ear, or otitis externa, is a painful ear infection caused by trapped water and bacterial growth. Learn how to prevent it with simple drying habits and what treatments actually work-backed by clinical data and real patient outcomes.